|

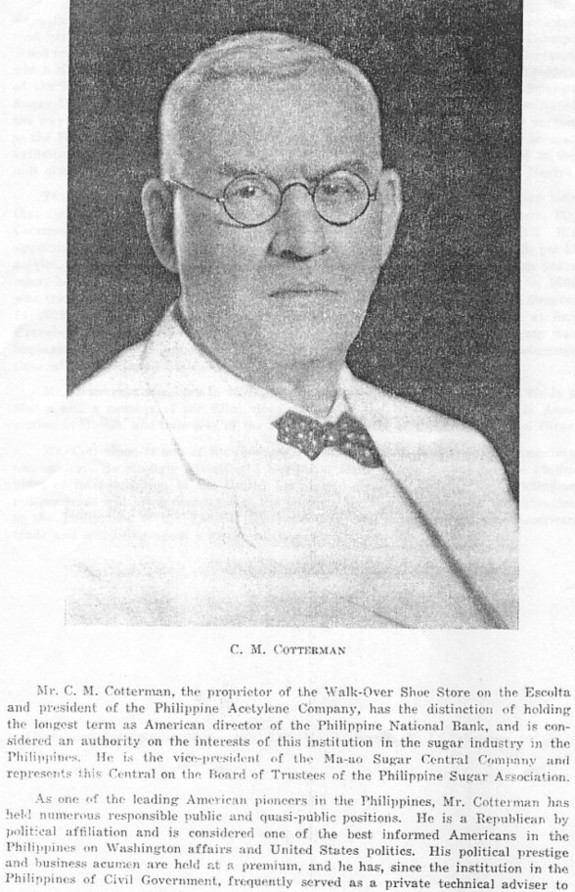

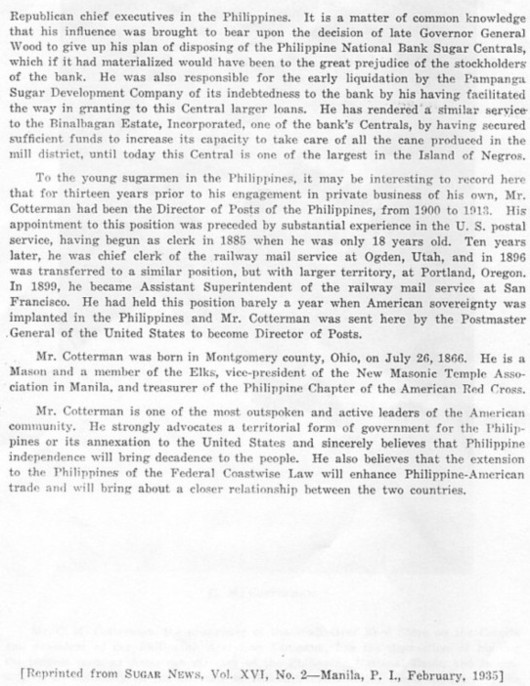

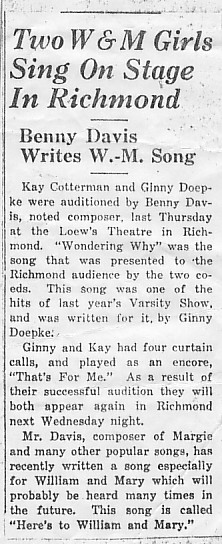

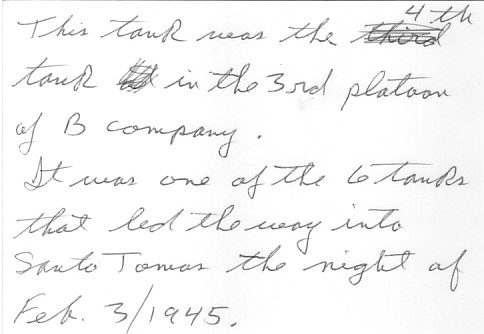

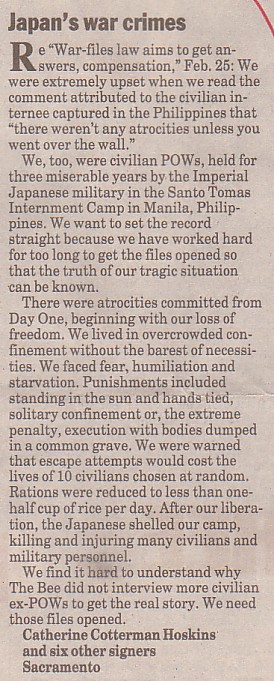

317 39th Street Sacramento, California 95816-3427 (916)451-1519 Copyright 2003 The first questions I am asked when folks learn that I was born and reared in the Philippines are: Was your Dad in the Military? Were your parents Missionaries? No – to both questions. Let me start with a geographic description of the Country where I was born and called my home for 24 years: The Philippine Archipelago sits on the far western rim of the Pacific Ocean – south of Japan and north of Borneo – bounded by the Pacific Ocean and the China Sea. There are 7000 Islands in the Archipelago – many of them stepping stones to be seen when the tide is low. About 1500 Islands are inhabited. The two largest Islands are Luzon, the northern most, and Mindanao to the South. The Capital City of Manila is located on Luzon – and that is where I was born.   After the Spanish-American War came to a quick end when Admiral Dewey sailed into Manila Bay in 1898, the Philippine Islands (as they were called then) became a Territory of the United States of America. The McKinley Administration sent my two Grandfathers (both natives of Nebraska, but never knew one another there) to the Islands – one to restore and rebuild the Penal System, the other (C.M. Cotterman) to restore and rebuild the Postal System. They were told they could take their families and after had fully completed their missions (which took several years) and trained Filipinos to take over, they could return to the United States. However, both men had fallen in love with the Philippines, and both decided to go into private enterprise, settle down and call the Islands their home.   One Grandfather went into the Publishing Business with the Manila Bulletin – a long respected newspaper that is still in print today. The other Grandfather (C.M. Cotterman) bought a hole-in-the-wall shoe store and made it into a very successful business known as the Walk-Over Shoe Store and Men’s Haberdashery. Over the years he added Women’s Shoes and Accessories.   My mother and father grew to adulthood and were married January 6, 1914. I was the youngest of their 3 children. My dad was a mechanical engineer and could not get excited about selling shoes in his father’s store. Together they bought a small Acetylene plant and made it into a very needed business – manufacturing Oxygen, Hydrogen and Acetylene. Dad was in his element doing what he was cut out to do. Life in the Philippines was comfortable and prosperous. The City of Manila was very cosmopolitan – inhabited by Americans, British, Australians, Canadians, Spanish, Dutch, French, Germans, White Russians, Chinese, and Japanese. The Filipinos were a gracious and accommodating host. After the Spanish-American War and the Insurrection that followed, Manila flourished. There were merchants, bankers, engineers, teachers, lawyers, doctors, nurses, architects, builders, manufacturers, jewelers, grocers, open-air markets, cold storage for imported meats. Good schools were established – education was a very important issue. The Philippine Legislature was bolstered by American rules of democracy. Yes, it was a happy, productive life filled with adventures and advantages for the kids growing up. In 1938 I went half way round the world to attend the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia. It was an ideal place for someone like me who had grown up out of this country – it was the Cradle of the Nation, a thrilling place to be educated. After 3 years away from home, I was quite homesick. I wasn’t sure of the direction I wanted to take in my studies – so I asked my parents if I could take a leave of absence, go home and perhaps return to college in the Spring semester. It was agreed and I flew to Manila on Pan American Clipper. I landed in Manila in June of 1941 – poor timing.  Richmond, Virginia Newspaper January or February 1941   Here is a recant of Kay’s trips between Manila and Virginia, to attend college at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, VA: 1938 – Manila to Vancouver, Canada, on the Empress of Canada. June 1940 – Return to Manila. Flew on the M-130 Clipper out of Treasure Island. This was the 200th round-trip of the Clipper flights. September 1940 – Return to school. Flying on the B-314 from Manila to San Francisco. June 1941 – Returned home to Manila on the M-130 Clipper. Click here for Catherine's love affair with Pan American Airways. It was plain to see something was in the air. Ships loaded with military dependents were sailing every week for the United States. Incoming ships brought in young Air Corps Officers and other military personnel. Black outs became routine. Civilians were not ordered to leave. My family – 4 generations, 17 members – chose to stay in Manila, the only home we knew. I can remember the day all of the adults sat down together at the dining room table and discussed the question: to leave or not to leave. When my grandfather announced that he was staying but he would pay the passage for anyone who wanted to leave for the States – everyone else joined in on his decision. Little did we know what was ahead of us. But, for the next few months, life went on in fairly normal fashion. We had been told that equipment and personnel would soon be on the way across the ocean to support and defend the Philippines when and if trouble started. Then came the 7th of December, 1941, and the Japanese launched their infamous attack on Pearl Harbor – the help promised us was re-routed to Australia. It was, indeed a sad day. Immediately following the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japanese bombs started falling on the Philippines, starting on northern Luzon – Camp John Hay in the Baguio mountain province – then Clark Field; Nichols Field, Cavite Naval Station, Manila Bay, Tagaytay Ridge south of Manila. Our anti-aircraft was obsolete and ineffective against the Japanese bombers in their elegant formations. The Air Corps officer I was dating assured me that the only thing we had to be afraid of was falling Japanese Aircraft. Boy, was he wrong. During night and noon bombing raids, not a single enemy bomber came down. My brother fashioned a cozy bomb shelter under our house which stood high off the ground. We were fairly sure we would not be a target for a direct bomb because the Japanese were bound to want my dad’s Acetylene plant with the hydrogen and oxygen tanks and machinery in tact for their use. Our home was right next door in the same compound. Not too far away was the Manila Gas Company and the Philippine Refinery – all necessary to the Japanese when they invaded. We did feel safer in the shelter because of shrapnel. To end the bombings and further destruction, Manila was declared an open city as American and Filipino military pulled out of the Capital to make a last stand on the peninsula of Bataan. Civilians were warned to stay calm, not resist and to do as they were told by the invading Japanese forces. Help was not on the way as we were led to believe. My Dad was told by our military command to release the hydrogen and oxygen from his tanks. That was scary. I can still hear the hissing sound of escaping gas from those tanks which had been placed outside in the open air. It was at the start of Christmas week when the open city began. Not a very happy Christmas – although we tried to make it merry for the little ones. My dad decide he did not want to have any liquor around for the Japanese – so the men of the house reluctantly carried the contents of a well stocked bar out to the estero, “canal”, that ran by our property, and dumped them into the water. On New Years Eve we toasted with water from the tap. Prospects for the New Year were very glum. On the 3rd of January 1942, the Japanese Army entered the city of Manila. At noon that day, an officer, an interpreter and six war weary soldiers with fixed bayonets came into our home. We were told that we had one hour to pack one bag each – they would be back when the hour was up. We scurried about trying to think of what we should take. It was an hour of heartbreak, knowing what we must leave behind. When the officer and his men returned – he ordered my Dad to open the house safe and when Dad did so – the little man took all the jewelry and scattered all papers on the floor. Then he told us that we could take 1 car and the truck from the plant – but – both drivers had to return or else. After issuing his demands in a frightful manner, the officer indicated that we all must leave the premises. Then my wonderful mother stepped forward and with great determination she said: “We cannot leave here without a pass to get us through any sentries on our way to Pasay” – my grandfather’s house was still in a place outside Manila which had not been disturbed yet. It was about a 30 minute drive and Mother was adamant that the officer give us a paper that would get us through any barriers. The interpreter told the officer who looked at Mother with obvious annoyance. Then he drew his sword and we thought for sure he was about to do her in. But, instead, he handed her his sword and demanded that she carve out a plan of our direction in her beautiful hardwood floor. She did and explained her plan to the interpreter. She handed back the sword and the officer demanded paper and pen, which she found for him. After hastily scribbling on the paper in Japanese – he handed her the note. As they glared at each other, it was easy to see he had great admiration for her spirit. We were hastily dispatched down the stairs and out to the drive way where we climbed aboard the truck and Chevrolet sedan with our Chinese Amahs, our luggage and our family pets. The drivers were once more given strict instructions to return with the vehicles with in hour. Our Filipino employees with tears rolling down their cheeks waved us goodbye. We never really knew what the pass the officer gave Mother said. It could have been an order to shoot on sight. But it got us through sentry posts on our way to Grandpa’s home in Pasay. I shall never forget the sinking feeling I had as we drove away from our beautiful home – for the very last time. Three days later we were picked up at Grandpa’s and taken to the Rizal Stadium where we stood with thousands most of the day in the sun, being processed. Once more we climbed onto old school buses and trucks commandeered by the Japanese from all over town. Mother, Dad and I found ourselves on a bus for the Immaculate Conception Convent. In about 25 minutes we were driven through the gates of the University of Santo Tomas – an historic University founded by the Dominican Order of the Roman Catholic Church in 1619, which makes it older than our Harvard University, the oldest in this country. Although the University remained under the Spanish Dominican Priests, it flourished under the American Regime. The campus is about 50 acres in size and its location an excellent one. But the buildings quite obviously were never meant to house 4000 men, women and children. Besides Americans, there were British, Canadian, Australian, Free French, Dutch, and other allied civilians such as White Russians. That first night was filled with chaos and despair. Hot and hungry and tired, everyone tried to find a space to sleep and feed to eat. We had been told to bring 3 days supply of belongings and feed. Little did we know that those three days would stretch into 3 years – without basic needs or comforts and constantly being degraded and humiliated. We had 3 things in our favor: The Japanese allowed families to stay together in the same Prison Camps – not sleep together, but kept together as a family unit. In the English and Dutch Colonies – Singapore, Java, Sumatra, Jakarta, Borneo – it was a different and sad story. The men were taken off to slave labor, the women and children had to do the best they could in different camps – and they suffered great hardships. Often times the women and children had to walk from one camp to another – under guard, and weak from hunger. In the Philippines they took a different track. We were ordered to set up our own Central Committee made up of prominent business men – known to the Japanese. This edict truly saved us – every one pulled together and followed the rules set down by the Committee at the request of our captors. Also in our favor was the climate. It was in the tropics – we never had to worry about severe cold weather or snow. Once in awhile a typhoon would pass through and cause loss of power and floods and days of incessant rain – but we could deal with that. Then we had the loyalty and support of the Filipinos – much to the chagrin of the Japanese who tried to no avail to convince the Filipino people they had been saved from enslavement by the United States. As long as they could, the Filipinos brought needed supplies to the Internees. Eventually the Gate was closed permanently – we were denied communication with the outside. From the beginning we were warned not to try escape. Unfortunately, 3 Australian men went over the wall and made an attempt to escape. Within one day they were caught. They were brought back to Camp under armed guard and forced to stand many hours in the sun so that we could see them. In spite of many attempts to defend them, they were taken away and executed. Then the proclamation was made – any future escapes would be punishable by death including 10 Civilians picked at random. Now we knew where we stood as far as discipline was concerned. Communication with the outside, in any manner was punishable by death. Many times, usually in the middle of the night, we were awakened by bugle call over the loud speaker. We would be ordered to get up and stand by our cots with our bags open on the cot. It took a very long time for the midnight inspection to be completed. The officers in charge of the inspection would stomp into the room issuing instructions as they examined each open case, or box, and ran their hands along the walls examining them for wires and in belongings searching for radios or even parts of radios. These inspections were as bad as the bed bugs. Standing Roll Call twice a day was mandatory – 6 am and 6 pm. You had to be in front of your room, prepared to bow as the inspection took place. Each room and shanty area had a monitor who was responsible for assuring the guard that all were present and accounted for – unless anyone was in hospital or signed out of that room to another location temporarily. No ifs ands or buts were acceptable. I mention shanty areas. As the population of the Camp expanded, it was obvious that the Japanese should approve the making of shanties to house some of the overflow. A shanty was put together with bamboo, nipa and sawali. It was a fire hazard, so strict rules were enforced to avoid the possibility. As the shanties went into place, men were allowed to live in them, thus relieving some of the congestion in the buildings. Eventually it was decided wives and children could join the men in the shanties – a great solution to the crowded dormitory conditions. Letting families be together was a big help toward morale boosting. Each shanty area had a name: Glamorville, Picadilly, Barrio Foggy Bottom, Jungletown, Shanty Town. Weeds and grass had to be cut down; fires could not be started with any kind of fire enhancer. Everyone between 18 and 55 had to hold some kind of job in order to receive a meal ticket – except for those with a disability or heart condition. The men in their 20s and 30s took over the heaviest tasks – garbage detail, cooking, lifting and cleaning the large cooking pots, mopping kitchen and bathrooms, unloading supply trucks. The sanitation department had a tremendous task. Older women did rice cleaning detail. Younger women without children cleaned vegetables, monitored bathrooms, worked in the vegetable garden and assisted the Army and Navy nurses (later referred to as the “Angels of Bataan”. The Navy Nurses were transferred to Los Banos in 1943). I worked first in the Children’s hospital ward and then as a nurse’s aide in the tubercular ward of the Isolation Hospital. I did vegetable cleaning, too. I dropped peelings into my lap and carried them to my brother’s shanty where his wife put them into the family Sunday pot. The time came when the order came down to just wash, not peel, the potatoes which put an end enhancing Sunday supper. The Camp was well organized – we had to be to survive. At the top of the organization chart is the office of the Japanese Commandant. Under his command is the Advisory Committee, The Executive Committee and the Philippine Red Cross members in charge of the kitchens, the food and the supplies. Under these follow Social Services which include welfare, education, recreation, religion, entertainment, library, lost and found; Administration which handled discipline, census, work assignments, information and more; Essential Services: Sanitation and health, Hospitals, Electrical and Fire prevention. Everyone pitched in to the best of their abilities. Women with young children were expected to keep them in hand and to keep their quarters clean. Grade school and High School aged kids were fortunate to have teachers available to carry on education under pitiful conditions. Classes were held in the open air. Grim was the word for our situation as time went by. Children and the elderly and the tubercular patients were given the best nutrition available: Carabao milk, eggs, meat. When one of our early commandants had to leave us, he gave a speech to the entire camp. I think Hayashi had liked Americans at one time – when he was 19 years old and visited Canada and America. His tour of duty was short because he was a little more lenient than he should have been. In his farewell address he said, and I quote: “As long as we are victorious we can afford to be magnanimous.” That was the clue he knew we would pick up on. And we did. We knew that as bad as it was now – we would know when the tide had turned in our favor when the screws tightened and tighten they did. Rules changed often and then every day. In 1943 a new camp had to be established for our overflow. The young men were sent first to put up dormitories on the campus of the University of the Philippines in a town 75 miles south of Manila called Los Banos. It was the Agricultural campus located in rolling hills. Soon the men were followed by volunteer families, wives and girl friends. Daily rations were being reduced constantly – in both camps. Medical supplies could not be kept up. Malnutrition, infection and starvation were the causes for deaths. Fortunately, early on, the Japanese who are very wary of epidemics in their own country, decided to bring in a medical force to give all internees inoculations against cholera, typhoid, diphtheria. We were lined up to take these shots wondering if those needles were filled with poison. Because of their fear of rampant epidemics – our camp was saved from them. We did have a small breakout of typhus – and, unfortunately, polio hit us – only four cases, one of which was fatal – a little girl. We faced starvation without hope of rescue. Then, one night in October of 1944 – the man in charge of giving us orders for the next day over the public address, called our attention. Everyone knew that a rice shipment promised us was 2 weeks late. Don Bell, the announcer, said for all to hear: Men on rice detail must be at the back gate at 7 am to unload the rice truck – he paused, and then added “Better Leyte than never.” Everyone gasped but we could not show emotion. We knew our forces had landed on the Island of Leyte – but we could not show the Japanese in any way that we knew. It would only be a matter of time – American planes were in the sky over us. Our rations were diminishing to less than ½ cup of rice per day. Four months later on the 3rd of February 1945 at the 6 pm roll call, leaflets came from the sky saying, “Roll Out The Barrel” and another one saying, “Christmas Is Here” – later the 44th Tank Battalion of the first Cavalry Division, roared up to the gates – it was 9 pm – and the lead tank called out are you Americans in there? And the screaming answer back was: Hell, yes – come on in. And in they came – 7 gorgeous Sherman Tanks, with the first one bearing the name “Battlin’ Basic”.  (anyone know either of these guys?)  The battle for Manila had begun and it was horrendous. Fires and demolition destroyed the beautiful City once called the Pearl Of The Orient. The destruction was second only to Warsaw, Poland. Eventually, when it was safe, the young families and single folks were flown to Tacloban on the Island of Leyte. Because my mom and dad were not ambulatory, we had to wait until Manila Bay was cleared of mines and a ship convoy could be brought in to take us away. We lived in the camp until 10 April, 1945, when we were transported to the Bay and taken out to the ships on landing craft carriers. There were 12 ships in the convoy escorted by 3 destroyer escorts. My parents and I were put on a Norwegian Freighter which had been converted into a troop transport/hospital ship. It was called the Torrens – and I shall never forget that ship and its gallant crew. Our first stop was Tacloban. When we left that port, our ship was separated from the convoy and with one destroyer escort we sailed off in a different direction – down under. Because we were the lightest ship, our mission was to pick up military personnel from Islands such as Manis, the Admiralties, and New Hebrides. We were 5 weeks at sea – and faced one submarine scare. We could feel the impact of exploding depth charges. The general alarm brought the ambulatory on deck to emergency stations – wearing Mae Wests. Fortunately, we did not have to abandon ship. On the 15th of May, 1945, we arrived in San Francisco Bay. At midnight when we went under the Golden Gate Bridge there were tears and screaming as the Captain blew the horn. While at sea, President Roosevelt died and then followed the glorious V E Day. The War in the Pacific would not be over for another few months. When we landed in San Francisco we were met by a tumultuous crowd and a wonderful band playing patriotic tunes – and welcoming songs. We had lost everything – our home, our business, our sentimental possessions – but we had our lives. We had to pull ourselves up by the boot straps and start over, which we did. We learned to never take our freedom for granted. When you lose freedom it is the most devastating experience you can endure. Freedom is not free – Please do not take it for granted. That is my message to you today. What happened to American Civilians living and working abroad should never happen again. All the Japanese camps held a total of 13,993 Civilians ---- 11% of these died before liberation.   or would like to be added to the POW/Internee e-mail distribution list, please let me, Tom Moore, know. Thanks! |