THE LONG MARCH INTO OBLIVION

An American Machiavellian Tragedy

and a U.S. Government Disgrace

The Federal Government is guilty of 66 years of humiliation to the former U.S. POW's serving in the Asian Theatre during World War II.

Throughout this story of tragedy and humiliation runs the thread of a beautiful and miraculous love story.

Dedicated to the men who couldn't tell their stories and no longer can.

At nineteen I met the love of my life. I lost her. I went to war. I lived through Hell with my buddies during WWII as a Japanese prisoner of war.

I came home overwhelmed to find that God answered prayers that I made when I was a prisoner in the Dungeons of ancient Fort Santiago. God saved my sweetheart for me to hold in my arms once more. We were married on Christmas Day, 1945.

My story also describes how my buddies and I were abandoned by President Roosevelt, suffered brutality and murder under the Japanese military. We did receive some mercy from some Japanese military bur more so from Japanese civilians at the risk of their lives.

The War Story

The U.S. government abandoned American fighting forces in the Far East at the beginning of World War II. This betrayal began in secret in December 1941 when President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill decided to desert their Far East Forces, concentrating their efforts on Hitler in Europe.

As the Pacific war began, the U.S. military forces courageously held General Yamashita and Homma at bay. Like the men of Valley Forge, the men of Wake Island, Bataan Peninsula and Corregidor Island fought under the most desperate conditions. They fought long enough to give General MacArthur the time to amass supplies and manpower to defend Australia. The loss of Australia for the Allies would have been a major disaster.

The unsuccessful attempt to conquer Australia enraged Tojo, the "Razor," Premier of Japan. He caused the murder of 37% of the American POWs in East Asia, compared with 1% under the Germans in Europe.

At the end of the war, while being repatriated, the POW survivors continued to be humiliated at the hands of their own. The American military officers forced the returning POWs to sign papers preventing them from ever revealing their stories. Welcome home POWs!

The Machiavellian tragedy began in 1951. The U.S. government agreed to compensate their POWs for the mistreatment they received under the Japanese. The 16,000 POWs are now less than 1,000 and are still waiting for the promises that were never kept.

In 1951, the POWs were sacrificed during negotiations of the Japanese Treaty at the end of the War. The Allies waived Japan's responsibility to compensate the POWs in the interest of not breaking Japan's economy. At those negotiations, in lieu of Japanese compensation, the Allies made a promise that they would compensate their ex-POWs. Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, a member of the negotiations, declared, "America will take care of its own."

All of the Allies, with the exception of the United States, kept that promise. England said, "We did it as a matter of Honor." In May 2006, South Korea compensated the forces who had been enslaved in Japan's wartime industry. In May 2007, the House of Representatives passed a bill to compensate the people of Guam for the treatment they received under the Japanese.

The question to be answered after fifty-six years of waiting for the U.S. Congress and the Executive Office to honor Henry Cabot Lodge's declaration, will it ever happen? If not, then the surviving POWs and their widows, unrewarded and in humiliation, must continue the "Long March Into Oblivion" until they are all dead.

Now, Back To The Beginning Of My Story

Hi! Hi! My name is Donald Douglas Rutter. I was a radioman in the United States Navy when I surrendered to the Japanese military in Manila, Philippines. From January 3, 1942 to September 8, 1945 I was a slave of Hiro Hito, the Emperor of Japan.

But I am ahead of my story. I would like to begin with my childhood as a barefoot country boy with cheeks of tan.

At the age of eight my divorced mother and younger sister moved from the East side of Detroit to a small farming village on the shore of a lake. We lived in Michigan Center, southeast of Jackson for four years.

With the help of a kind retired man, by the age of ten, I was already an excellent fisherman with hook, bobber, sinker and bamboo pole. During the winters I fished through the ice. Most of the meat on our table was the fish I caught.

From age twelve to fifteen, besides fishing, I picked strawberries and tomatoes for three cents a quart for local farmers. In the winter, I made money trapping mink, skunk and muskrat. Now and then, I didn't go to school for a week until Mom could wash away skunk perfume with the aid of Fels Napha.

In 1933 we moved to Jackson and like many impressionable teenagers, I got mixed up with the wrong kind of guy. In 1934, at the age of 15, we took someone's car for a joy ride. The police called it stealing a car. Fortunately for me, my mother sang in the choir of the First Baptist Church with the juvenile judge and the juvenile probation officer.

At sixteen, I and that same guy ran away from home and ended up in the Grand Island, Nebraska county jail for twenty-seven days for vagrancy. While there, I never ate so well in my life. From Nebraska, I came back forlorn to live with my father and stepmother in Lansing, Michigan. That wonderful woman, my stepmother, brought me in and was able to change the course of my life. For her loving care, I am eternally grateful. As for that guy I ran away with, the last I heard about him he'd gone to prison.

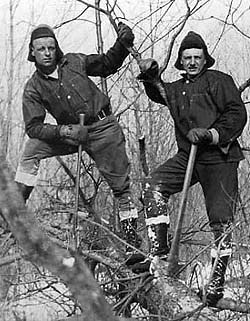

The Woodsmen

The WoodsmenBuddy & Don (on right) - 1937

In 1937, I quit school in the eleventh grade and joined the United States Civilian Conservation Corps, a federal program designed to give work to young men and WWI veterans during the Great Depression. I was in the CCC's for two years. There were 200 men in a camp. They lived in tarpaper-covered wooden barracks. Army officers were in charge of camp regulations. The Army also provided food, clothing, medical care, recreation and pay of $30.00 a month. Of this, $25.00 was sent to help the enrollee's folks. The enrollee got to spend the remaining $5.00.

Most CCC camps were in the National Forests. The US Forest Service provided the work for the men, consisting of planting trees, fighting forest fires, building fire trails, constructing roadside rest areas as well as work in fish hatcheries, animal research, dam building, and bridge building.

CCC Camp Raco #667 - 1937

CCC Camp Raco #667 - 1937In September, 1937 I was sent to CCC Camp Raco #667 located on the south shore of Lake Superior in the Hiawatha National Forest of Michigan's Upper Peninsula. The camp was 25 miles from Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan. The land surrounding Lake Superior was the hunting ground of the mighty Chippewa Indian Nation, the subject of Longfellow's fabled Hiawatha, the land of the sky blue water. This land has made a strong impact on my life.

In January 1938 I was transferred to Fort Brady in Sault Ste. Marie, the headquarters for the 60 CCC camps in the Upper Peninsula. There I became a chauffeur for the government officials.

Don, now an official car driver - 1938 |

Elaine Marie "Dolly" Aho A Kindergarten Teacher Gwin, MI - 1938 |

In May 1938 I drove to Camp Escanaba, close to the little town of Gwinn, Michigan. Here I met the love of my life, a kindergarten teacher named Elaine Marie "Dolly" Aho. We fell deeply in love at first sight. The first evening we went dancing, and she fell into my arms.

At the end of the evening we stood by a wrought iron gate connected to a fence surrounding the front yard where she stayed. A full moon made it daylight. Oh, God. It was just like in the movies. I placed my arms around her waist to start telling her how I felt about her and she started to cry. In an instant her face fell on my chest. Now she was sobbing, "You made me love you. Now you're going to leave me and I will never see you again." While she was sobbing against me, I stood there in shock. For the first time in my life I was holding a beautiful woman in my arms who was crying over me. No one ever cried over me ... No one. I felt totally out of my element. For the moment, I was paralyzed. Finally, I came to my senses and, I took her face in my hands and bent her head backwards until we were face to face. Then, I kissed her eyes. I kissed her tear-stained cheeks and her mouth that was wet with tears. I kept kissing her ... and kissing her ... and kissing her. After a while she wilted into me with a sigh. I said, "I'm so in love with you, I don't know if I have the strength to leave your side to go on to do what I must do. This, I swear to you. The only thing that will stop me from returning to your arms is because somehow I've died." As I gently and reluctantly began to separate myself from her arms more of her tears began as she pleaded, "Oh, Donald if you truly love me then you must come back to me." Once more, I kissed away her tears while begging her to trust me. With the most wrenching feeling I had ever experienced in my guts, I walked backwards away from her saying, "I love you," over and over again. Something deep inside me whispered, "This woman is yours. She will be your soul mate even throughout eternity." But to marry her I had to get out of the CCC's and get a job.

In January 1939 I requested a transfer back to to Camp Raco. In August 1939, on a sunny Sunday afternoon, I stood on the beach of Lake Superior, the greatest single body of fresh water in the world. When her clear water turns dark gray she is the most treacherous of all waters. But that day her beautiful breast was calm. Her water was dressed in sky blue... She was gorgeous.

Suddenly an indescribable feeling flooded my body from head to toe. During that spell the scene surrounding me seemed to call out, "We are a Creation!" "If so," my mind answered, " There must be a Creator!" I looked into the sky above and cried out, "God! If you're still there, will you please use me?"

By sight or sound there was no answer. The spell slowly faded away. I fought to prolong it, too no avail. When it was gone it left me shaken. With the hope that something might still happen, I lingered awhile longer. At last, with no further sign, I left, listening to the waves of "Gichee Goomee" caressing her shore and the sound of birds singing in Hiawatha's primeval forest.

As I walked away my mind was in turmoil. What had caused me to cry out to empty space? I never did anything like that before. But deep inside somehow I felt that someday I would learn my outburst had not been made in vain.

On September 1, 1939 my hitch was over. I left the CCC's with an Honorable Discharge and hitch-hiked back to my home in Lansing to find a job. I had served two years, a special experience in my life I knew I would always cherish. As I walked the Camp road to M-28, where I would begin hitch hiking my way to my father's house in Lansing, the reality of my new situation began to take hold. It was now causing butterflies buzzing around in my stomach.

I had no job and no car. The only money I had in the world was the thirty-dollar mustering out pay I just received. The only civilian cloths I owned were the suit, shirt, socks and shoes I was wearing. In the barracks bag I was carrying was the well-worn WWI army cloths I was issued when I joined the C.C.C's.

Comes The Sound Of The Four Horseman

As we passed through Gaylord, Michigan, we heard on the car radio that the Germans had invaded Poland. With that act the seeds of WWII began to sprout. When I arrived home I went to my uncle who had been an artillery officer in WWI. I was concerned about the invasion and how it would affect me. I asked him, "What do I do now?" He told me we would be in this war and I had two choices: I could voluntarily join the service now and become a trained serviceman ready for battle. Or, I could wait to be drafted and end up as cannon fodder in some God forsaken spot.

Don, a new recruit

Don, a new recruitat Great Lakes Naval

Training Station

March 1940

Since I already had experience serving under Army command in the CCC's, I was a prime candidate for the service. All they needed to do was teach me how to use a bayonet to be ready for battle.

On March 20, 1940 I signed up with the Navy for 6 years and had to leave Elaine behind. I was eventually assigned to the USS Pope 225 Naval Destroyer in the Philippines. In April 1941, I was sent back to the radio school at Cavite Naval Yard for training to become a radioman.

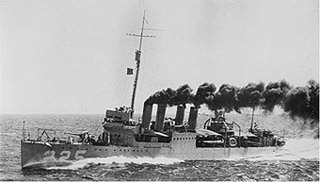

Don is transfered to the Destroyer USS Pope 225,

a "four piper", a part of the old Asianic Fleet

in January 1941

..."WE ARE UNDER ATTACK... THIS IS NO DRILL!"

It was in Cavite, on December 7, 1941 that I heard the radio message from Pearl Harbor, "We are under attack. This is no drill." At that moment, my life, along with the rest of the world, was dramatically changed. The next day we received the message that the Marines were under attack on Wake Island.

"Dante's Inferno" - the total destruction of Cavite Navy Yard by

"Dante's Inferno" - the total destruction of Cavite Navy Yard byJapanese bombers in December 10, 1941

Dante's Inferno

On December 10, at noon, 54 Japanese Betty bombers began bombing Cavite navy yard. The bombing lasted for 45 minutes. At the end of the assault, 1,600 Navy personnel, along with civilian staff, were killed or wounded. By 3 o'clock the fires and explosions of ammunition turned the Yard into a "Dante's Inferno." Admiral Rockwell ordered all hands to immediately abandon the yard. The loss of Cavite navy yard placed the Asiatic fleet in "harms way," without the possibility of resupply.

I was put aboard the PT boat #41 to replace the radioman killed in the bombing. Now loaded with every hand we could carry we passed by the eastern tip of Corregidor Island, which guards the entrance to Manila Bay, running to Marveles Bay, two miles across the channel from the fortress on Corregidor Island, thirty miles from Cavite.

There, I was replaced by a chief radioman who outranked me. I was sent back to Manila by road around the north end of the bay to be assigned to the Office of Naval Intelligence and Censorship, now located in the Yamashita National Bank.

I heard from the KGEI overseas broadcast from San Francisco that on the afternoon of December 7, 1941 America lay stunned over the horrible losses at Pearl Harbor. From Sitka, Alaska to San Diego, California in the West Coast, everyone was in a state of paranoia with the rumors of an Japanese invasion of the mainland.

The Deserted Allied Forces Begin The Battle With Japan

The Allied forces were spread thin across the Pacific. Americans were on the islands of Wake, Guam and the Philippines, with The American Lost Battalion in the East Indies. Canadians were at Hong Kong. Australians, British, and New Zealanders were in Singapore and on the Malayan peninsula. Also in the East Indies were the Dutch and the Javanese. The USAFFE and their allies didn't know that Roosevelt and Churchill had decided to abandon their Far East forces to concentrate on the war with Hitler. With no chance of resupply or reinforcements, the USAFFE and their Allies were doomed.

The world wondered how the Americans would stand up against the vaunted Japanese Samurai who already had conquered much of China and all of Manchuria.

The Long March Joins The Marines On The Isle Of Wake

On December 8, 1941, Wake Island radioed they were under attack by a Japanese Naval force. This was the first hand-to-hand battle in WWII.

After the war, I learned the results of that battle. The Japanese Imperial Naval force was comprised of 15 ships, including four heavy cruisers. Their combined firepower was thirty-six 9-inch naval guns. The Japanese Naval Landing Party (JNLP) was close to 10,000 men. Against the JNLP were 400 American Marines, with 6 land based 5-inch Naval guns.

On December 23rd, after 15 days of intense fighting, much of it hand to hand, the Marines were out of ammunition and overrun. As they were led away as POWS, the "Long March into Oblivion" began. They left less than 100 of their buddies buried in the sands of Wake Island. They also left 5,500 Japanese military buried in those same sands. They left nine of the enemy fleet on fire, sinking, or lying on the bottom of the Pacific Ocean.

After the war, Japanese Commander Masatake Okumiya admitted that it was the most humiliating defeat the Japanese Navy had ever suffered.

Preparing For Battle In The Philippines

On December 25, 1941 to save the city of Manila, MacArthur made it an Open City. An open city means it is free of all military personnel and equipment, leaving it undefended. At that moment all military changed into civilian clothes and continued transporting supplies to Corregidor and Bataan.

On Dec. 29, the Japanese stood at the southern gates of the city, unopposed. We were ordered to destroy everything we could, including all the communication equipment in the RCA overseas office, the major civilian radio communication office. Others blew up the oil supply depot in Pandacan in the Manila Port area. That same day all military persons in Manila were ordered back out to Bataan and Corregidor by any means possible.

We commandeered small private boats. In the darkness we found that the bay was being blockaded by Japanese small boats with running lights. Unseen, we returned to Manila and in the morning we went to the U.S. High Commissioner's office. There we were given phony passports. At that time, the Japanese encircled the city but for some reason held off from entering the city.

On January 1, 1942, I was in a naval reserve officer's apartment across the street from the High Commissioner's office. He had destroyed his navy gear, using his business suit as his cover. I stayed up half the night trying to determine whether to hide behind my passport or surrender to the enemy.

In the morning I looked out the window in time to watch Japanese Army personnel lower the American flag and throw it on the ground. In its place they raised the Japanese flag. I will remember for the rest of my life that sickening moment.

All I had was the clothes on my back and no place to hide. If someone turned me in I would be shot as a spy. If someone tried to hide me and we were found, we would both be shot.

Goodbye To Freedom And All It's Charms

Finally, I realized I had but one way to fly... turn myself in. I destroyed the phony passport. I said goodbye as I left the apartment and crossed the street to what had been the high commissioner's office. I spotted the Japanese official running the show. I gave him my name, rank and serial number.

He asked in perfect English, "Why are you dressed in civilian clothes?" I said, "Do you see the column of smoke rising in the southwest direction? All I had went up in smoke right there."

He asked, "Do you have any American cigarettes?" "Yes," I answered, and we traded cigarettes. He told me he was busy and directed me to sit in the shade of the truck. (I thought, "I am now a prisoner of war, I'm a man without a country... welcome to the rest of WWII.")

Finally he came back to me and apologetically said there was a problem because they had no military prison camps. Being somewhat polite, he asked if I would mind going into a civilian internment camp they were setting up at Santa Tomas University, established by the Dominican Order sometime in 1600. Of course I agreed.

I'm A Captive In A School

The next day, January 3rd, 1942, I was taken to the Japanese Commandant officer at Santo Tomas. He spoke with a perfect English accent. He told me to follow the rules he had placed for everyone to see and to conduct myself as a gentleman at all times. Do that and everything would be "tophole." He added, please report to me once a week and he gave me my room assignment.

As I headed to my room my thoughts were in turmoil. I was out of my element. I had lost my ship. I was surrounded by civilians and their culture. Although I was a victim of circumstance beyond my control, I had a slight guilty feeling.

Don (no shirt) US Navy Age 23.

Don (no shirt) US Navy Age 23.Santo Tomas University Internment Camp - June 1942.

A short wave radio is hidden in the circuits of the turn-table

Most of all was the haunting knowledge that I was no longer the master of my fate. I had to learn how to stay alive as a POW. For the rest of my time in Santo Tomas I did everything I could to help ease the burden of the internees. I expanded the plumbing beyond two bathrooms to accommodate the enormous addition of people interned there. Then I rigged music equipment and got professional music shows going with American show people captured in Manila.

News about the war came through unusual avenues. Passes were issued to internees to go to the Philippine General Hospital for treatment. There they picked up news from the Filipinos in the hospital and brought the news back to Santo Tomas. Later, a small radio was smuggled into Santo Tomas.

Only a very few were trusted to know it existed. People believed the news still came from the outside. With that radio we were able to get what news was coming out of the fighting on Bataan and Corregidor.

Later in the fall of 1942 a very efficient underground was operating throughout the Philippines. The main couriers were the missionary Dominican Fathers from Spain. Spain was neutral. Ergo, the Fathers were able to go anywhere to minister to Catholics. This included Santo Tomas and most of the POW camps. It was amazing what was hidden underneath a Dominican Father's garments. They were men of the highest courage. Many died in trying to help others.

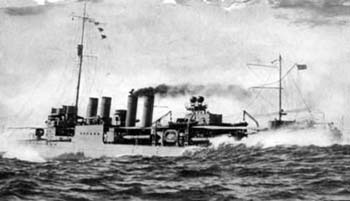

The Long March Joins The Navy At Balipapen Bay

In January 1942, we heard through the underground about a naval battle fought in Borneo. After the war I learned what happened there. In the dark of 3 a.m., four little American destroyers, a part of the old Asiatic fleet sneaked into Balikpapan Bay in Borneo to make mischief.

The "Little Sisters", at rest, tied in a "nest" - 1941 The "Little Sisters", at rest, tied in a "nest" - 1941 |

A "Little Sister", in "Harms Way" A "Little Sister", in "Harms Way"taking a 45 degree roll in "Tyfoon Ally" between Guam and the Philippines in the '40s. |

A "Little Bitch" taking green water on her bridge

A "Little Bitch" taking green water on her bridgein the '40s. |

Run "Little Bitch", Run!

Run "Little Bitch", Run!The Pope, running wide open, about 40+MPH |

The ships, built during WWI, were identical and known as "Sister" ships. Because of little or no armor, they were also known as "Tin cans." The trade off for the weight of armor was the ability to carry heavier more powerful engines. Their best defense was their maneuverability at high speeds. They carried 12 torpedo tubes and four 4-inch Naval rifle deck guns. The names of the sisters were the USS John D. Ford, the USS John Paul Jones, the USS Parrot and the USS Pope.

Also in the bay were twenty five to thirty Japanese transport ships at anchor. These ships carried thousands of Japanese troops and materials needed to invade Borneo's western shore. There also was a Japanese light cruiser, the Nara Maru, which carried nine 8-inch naval guns and six 5-inch guns. But the little sisters had an edge ... they could outrun her.

Fifteen modern Japanese destroyers, twice as large as the sisters, also were in the Bay. Their speeds were close to the speed of the tin cans but they needed twice the depth of water to float. The little sisters drew so little water they could run across a wet handkerchief. This gave them all kinds of advantages.

As the suicidal little sisters stole into the middle of the transports, their torpedo tubes were at the ready. There was enough light to make out the silhouette of the big ship against the night sky. Soon the sky became brighter as the victims of the savage little sisters began exploding and raging with fire.

Evidently the Japanese cruiser and her destroyers thought a submarine was firing at them, so off they went, the wrong way, looking for a submarine that wasn't there. Meanwhile, the sisters kept up their attack. When their torpedoes were expended, they unleashed their deck guns. Now the Japanese transports awoke to the fact that they were being attacked by surface ships, and started firing at the flash of the exposed little sisters' guns.

When practically out of ammunition, and with the looming threat of an angry Japanese cruiser and her 15 killer bees, American Commander Talbot ordered the concerned little sisters to pick up their skirts and run for their lives. At dawn, all hands looked to their sterns. The horizon was clear. The little sisters had gotten away clean.

As the one-sided battle raged, a Dutch submarine, lying-to at periscope depth, watched the show while waiting for its next victim. Its skipper reported the Americans had just left thirteen Japanese ships in fiery shambles. Meanwhile the Japanese cruiser made the fatal mistake of coming into the range of the submarine. The Dutchman fired her torpedoes and blew the cruiser all to Hell.

The proud sisters had outwitted a superior enemy force, becoming one of the U.S. Navy's greatest victories. All this happened in just one hour.

The Little Allied Fleets Sail Into Oblivion

Another battle followed sadly, the Allied Naval forces had no aircraft carrier. They were no match for the huge 18-inch naval rifles of the giant 35,000 ton Japanese "Kongo" type battle ships. The USS Houston, a heavy cruiser with her nine 8 -inch guns, was the largest ship of the little fleets. Like the Bismarck, she accounted for herself before she died. Ringed by Japanese ships, some on fire, some sinking because of her, the Houston was exploding, on fire and sinking. As she slipped, stern first, to her grave below, her forward turrets were still firing.

A Japanese ship picked up the survivors from the Houston. They were lined up on the foredeck of the Japanese ship so that the Admiral could personally salute each survivor, stating if this is the way the U.S. Naval forces fight, it is going to be a very long war.

A handful of ships got away. All too soon the majority of the courageous little Allied Naval fleets also lay on the bottom of the South China Sea. Now the chance for resupply or reinforcement was lost. As went the little allied fleet, so went the little sisters.

Our secret news source still gave sketchy details of what was happening on Bataan and Corregidor. I learned the rest of the story at another camp I was transferred to later.

By the end of March 1942 the only Allied forces in the Far East still in battle with the Japanese were the American and Filipino forces on Bataan Peninsula and the Island fortress of Corregidor. Both are at the mouth of Manila Bay on the Island of Luzon in the Philippines.

The Long March Joins Those Of Bataan And Corregidor

The Long March at this time joined the valiant men and women trapped on Bataan Peninsula. They would sing a song, "Oh, we're the Battling Bastards of Bataan, no poppa, no mama, no Uncle Sam, and nobody gives a damn!"

By the end of February 1942, General Yamashita, the "Tiger of Malaya," had raced down through the Malay Peninsula conquering everything in his way to silence the guns of Singapore forever. With that accomplishment, he began preparing his forces to invade and conquer Australia.

At that moment Australia was a sitting duck. Germany's General Rommel, the Desert Fox, had pinned down Australia's army in Africa. The remainder of the Aussies' overseas armies were either killed or captured by the "Tiger" as he over-ran the Malayan Peninsula.

Sixteen hundred miles northeast of Singapore, the raging battle for the Philippines held sway. That battle would soon thwart The Tiger's plans. The battle was between the Japanese invader General Homma and General "Mac" MacArthur, the defender of the Philippines.

Two factors were in Homma's favor. His troops numbered around forty thousand men and they were battle tested through years of fighting General Chang Kai Chek in China. Mac's Army was the combined forces of the American 31st Infantry, the Filipino Scouts (the main army of the Philippines), partly trained Filipino Army conscripts dragged out of boot camps at the last desperate moment, and American Army Air Force personnel who were trained to fight ... but only in the air.

Corregidor, guarding the entrance to Manila Bay, was defended by the Fourth Marines, the Army Coast Defense, and Naval forces (some off sunken ships) who were trained to fight... but only at sea.

As the battle on Bataan raged, Mac's forces fought the enemy with the voice of Washington ringing in their ears, "Help is on the way!" These courageous troops had no reserves. They fought with their backs to the South China Sea. They had no boats. Retreat was impossible.

Still the doomed American and Filipino forces refused to lay down their arms. They upset all the timetables that Japan's Premier Heideke Tojo, the "Razor," set for their annihilation. This fact embarrassed both Tokyo and Washington, who for different reasons wanted to end the battle for the Philippines.

For Tojo, the longer Bataan and Corregidor fought on, the more they gained sympathy and respect from the World, to Tojo's embarrassment. For Roosevelt, the longer Bataan and Corregidor fought on, the more the American people screamed for the relief of the gallant USAFFE.

There was a joker in the deck that favored Mac's men who had become acclimated to the curses of the tropics. Homma came out of the north directly into the malaria and dysentery infected tropical jungle. These infections decimated over 10,000 of Homma's men and put them out of action. It weakened the Japanese forces to a point that the American and Filipino forces were holding their own.

The Razor, now faced with an American and Filipino threat to the middle of his supply line and Homma's incessant call for reinforcements, was forced to order half of The Tiger's forces to aid Homma in crushing Mac's men. This action forced The Tiger to delay his plan to attack Australia.

FDR ordered MacArthur to Australia. Mac didn't want to abandon his men on Corregidor. Mac begged to take General "Skinny" Wainwright with him. FDR refused. It was a terrible mistake. Skinny's knowledge of the Asian mind was the best in the American Army. He cut his teeth in battle as a young officer in the Chinese Boxer Rebellion. For Mac, the loss of Skinny's help in Australia in forming battle plans had to be monumental.

Now outnumbered and without the promised help, the fate of Mac's men was sealed. On April 9,1942, out of ammunition, suffering from starvation, their ranks riddled by dead and wounded, the valiant forces on Bataan collapsed and became POWs. As they lay exhausted, they were unaware that in defeat they had won a tremendous victory. Yes, they had lasted long enough to slam the door to Australia.

The courageous men on Corregidor fought on, still holding The Tiger at bay. On May 5, 1942, their ammunition was spent. Now the guns of mighty Corregidor lay silent. The starving fighters on Corregidor went the way of those captured on Bataan. However in defeat, the men on Corregidor placed a lock on Australia's door. They gave Mac an extra precious month, time enough for him to organize the defense of Australia.

Skinny's genius, and his men's admiration for him, carried those of Bataan and Corregidor beyond the call of duty. Their actions prevented Yamashita and his troops from getting back to Singapore and changed the course of the war.

Later, military historians agreed that the sacrifice made by those of the Valiant USAFFE shortened the Pacific War by at least six months. More than 60,000 additional casualties were avoided and the cost of the Pacific war was spared many billions of dollars.

Without Australia it would have been a logistical horror. Men and equipment would have been shuttled from tiny island to tiny island, across the wide Pacific Ocean, greatly exposing the American supply line to the enemy. Instead, Australia became the funnel that successfully supplied the Allied forces to retake the Philippines at a great saving in lives and in money.

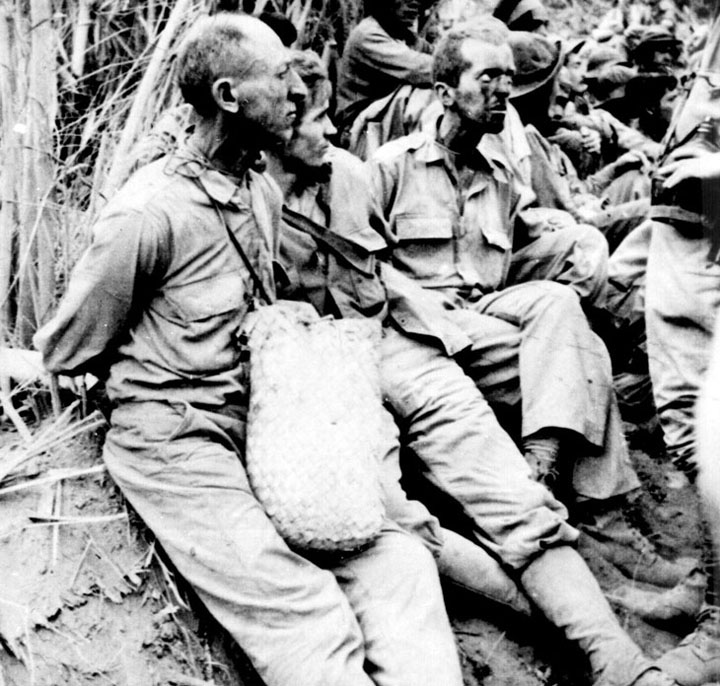

The Long March Joins The Death March Out Of Bataan

Now that Australia, the Grand Prize, was denied him, the Razor, in maniacal rage, denied the Allied POWs the Rights of the Geneva Conference for proper treatment of POWs. Instead he branded them captive criminals and sentenced them to life imprisonment at hard labor. At this point the Long March and the Death March would became one.

For the Battling Bastards, now POWs, Tojo's Sentence began with a vengeance as a soldier, starved and sick with malaria, stumbled and fell on the road that leads out of the Bataan Peninsula to Camp O'Donnel 90 kilometers away.

Before he could get up, five Japanese tanks rolled over the stricken man. As the last tank rolled away all that was left was a dark stained muddy blot on a dirt road. Emaciated men, their gaunt faces filled with horror, were forced by beatings to walk over that dark muddy spot. Thus began the Death March out of Bataan.

A man, crazed with thirst and intense heat, broke ranks to drink from a stream without permission. He was thrown into a cesspool. He raised his arm, as a call for help. A Japanese officer stepped up and severed the helpless man's arm with one cut of his sword. Fifty prisoners, thinking they had the right to drink, were machine-gunned to death as they ran for the water.

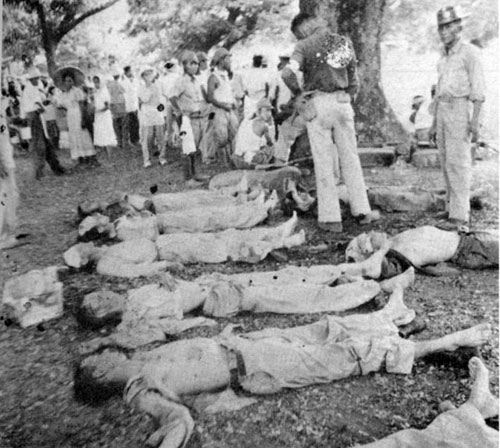

The faces of the Bataan "Death March" - April 1942

| PFC Sam Stenzler | PFC Frank Spear | Capt. James Gallagher | ||

| 31st INF, died in Camp O'Donnell on 5-26-42 | 31st INF (4th Chemical also) died on 7-18-43. in Fukuoko, Japan. After Abucay, the 31st INF was reinforced with members of the 4th and 7th Chemical. Chemical units are given Infantry training, so they were already infantry trained. | 31st INF died 4-09-42. Gallagher was killed soon after that picture was taken. His DOD is 4-09-42. |

Periodically along the 90-kilometer road to Camp O'Donnell, prisoners would fall down, too exhausted to walk on. As they lay, they were bayoneted to death, to keep them from trying to run away. Many prisoners died trying to save another prisoner.

Some of the Americans who died on the "Death March" - April 1942

Some of the Americans who died on the "Death March" - April 1942All along the road, brave Filipino men and women, especially the women, rushed out to give food and water to the desperate men staggering by, only to be shot or bayoneted to death for their Christian charity.

Please forgive me. I'm an old man now. My mind cannot handle all the horror that happened to those on that road to Hell. When the POWs reached Camp O'Donnel their numbers had been brutally reduced by nearly 12,000 of their buddies who had been murdered along the way.

At O'Donnel the Death March ended and the Filipinos were freed to return to their homes. Now the Long March moved in with the American POWs at Camp O'Donnel. In the next two weeks, 2,100 more POWs, denied enough food and medicine, died of starvation and disease.

Carrying dead Americans and Filipinos who died on the "Death March"

to Camp O'Donnel for burial - April 1942

The Long March then moved on to POW camp Cabanatuan #1, and 2,500 more POWs eventually died under the same conditions. There was no reason for them to die; food and medicine were just outside their prison gates. By summer 1942 the prisoners weighed an average of 70 to over a 100 pounds. As they died their naked starved bodies were buried, 90 bodies in a single pit, each day. Prisoners were beaten to death, for no legitimate reason, as they were used illegally as slave labor on Japanese military projects all over the Philippines.

The Door to "Hell University".

The Door to "Hell University".The Dungeons of Ancient Fort Santiago

January 1943

God Greets Me In Hell University

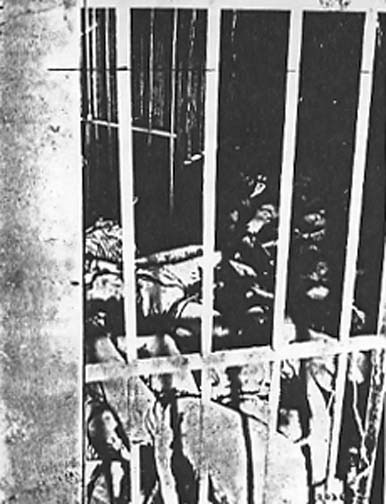

POWs were thrown into "Hell University," the dungeons of ancient Fort Santiago. The Spanish Conquistadors had completed the fortress in 1561 and the name Fort Santiago spread terror among the Filipino people. Local leaders of revolts were thrown into the Fort's dungeons, never to be seen again. In 1898, the United States captured the fort and turned it into a tourist attraction.

In January 1942, the Kempe Tai, Emperor Hirohito's personal army, captured the Fort and returned it to its former use. Many thousands were put to death there. In February 1945, the liberating Americans found that the Japanese Kempe Tai had packed the Filipinos into the cells so tight that over two thousand had died of suffocation.

It was not uncommon for the ungodly Kempe Tai to release a prisoner who they felt was not giving them all the information they wanted.

After a certain time, the Kempe Tai would grab their victim and throw him back into the dungeons again. This time they would threaten the victim with ten times the suffering he had suffered before. As most everyone has a breaking point, that moment would happen ... how exquisite the tactics of the Kempe Tai.

A cell in the Dungeons of Fort Santiago filled with

A cell in the Dungeons of Fort Santiago filled withdead Filippino prisoners who died of asphyxiation

February 1945

On January 12, 1943, the Kempe Tai entered Santo Tomas to remove all known military in the camp. There were about 25 or 26 men representing all the American military. Of course I was one of them.

From there we were thrown into the dreaded dungeons of ancient Fort Santiago. After seventy-eight days of interrogation, brutality and starvation, I was told by a Kempe Tai guard that I was to be executed in two days for crimes committed against the Japanese government.

As I sat in my cell, I became terror stricken. I was a rat in a trap. I had no way to escape or hide. I had just turned twenty-four years old on February 23rd. In desperation I called out, "Oh dear God in heaven, if you are still there, will you please give me the courage to face death?"

Instantly, loud and clear, a voice in my head said, "Now that you have prayed to me to be able to face death, did you ever think about praying to me to stay alive?"

Stunned, I began to pray again, "Dear Father in heaven, may I escape death in this hole in Hell? Father, can I still be alive at the end of this war? Father, can I go home and find Elaine Marie still there for me? Father, can we have a child? Father, can I live long enough to hold the child of my child?"

Two days later, I stood before a Kempe Tai officer and he said to me, "Your execution for espionage against the Japanese Government..." (When he hesitated for a moment to clear his throat, GOD disappeared and the knots in my stomach came back so strong the pain nearly doubled me over.) Then he continued, "...has been changed to life imprisonment at hard labor."

GOD reappeared. The knots in my stomach turned to butterflies. I became overwhelmed with elation that he wasn't going to kill me. I thought to myself, "Oh thank you, Almighty God, how great you are!"

Roy Bennet was in the Dungeons. He had been the editor of the English language newspaper called the Manila Bulletin. He was captured by the Japanese and told that if he would continue on as the editor he could come and go in Manila. Roy refused the offer and was promptly put in the Dungeons. For their sake the Japanese made a bad decision. Because the Filipino people saw a white man refuse to cooperate and take a stand against the Japanese, he was immediately jailed. The Filipinos marveled and were so impressed by the courage of Roy Bennet to act for their benefit that the Filipino people formed a large resistance force. The Filipinos resisted everything the Japanese wanted them to do in honor of Roy Bennet.

I met this man in the dungeon. After fighting broke out in a cell, a guard dragged a very small, frail piece of humanity to my cell and let him sink to the floor like an empty potato sack semi-conscious and covered with boils and open sores, sickening. My instructions were to take care of him. I gathered he was 45 to 50 years old. "Guard, guard!" I yelled. Instead of beating me for making so much noise and demanding a razor blade, bandages and iodine, they brought them, and two mattresses.

Roy and I talked a great deal and we got away with it in the "hospital" cell. Roy talked of the higher things in life, of freedom, national honor, the reason for the war, and things a typical sailor doesn't dwell on. He told me that he had been in Fort Santiago many, many months and didn't know if his wife and daughter were dead or alive. He said the Japanese kept him locked up because he refused to operate his newspaper under their censorship.

The Japanese weren't having much success winning over the citizens of the Philippines. Bennet's newspaper was important to them and he refused to bow to their demand to run it their way. He was a tiny man even before the Japanese threw him in the prison. He had been crippled by a childhood disease, probably polio, which left him with a severe limp and one arm lame. Although he was child-like physically, he was a giant of a man intellectually and a believer same as I.

In less than a week, all of a sudden they brought clean clothes, towels, and soap and took us to running water. I gave him a bath, and one for myself. I put on clean bandages, cut his beard (a foot long), shaved him, and trimmed his hair. He told that the clothes brought by his wife. I told him, "They are going to move you out of here." We were both exhilarated, getting ready to get out. He went back to Santo Tomas to his family, which took some of the heat off the Japanese. The Filipinos had won. He had a code of honor. I absorbed many things from him, the greatest man I ever met. I became a different person. I was so pleased that God allowed me to help Roy Bennet.

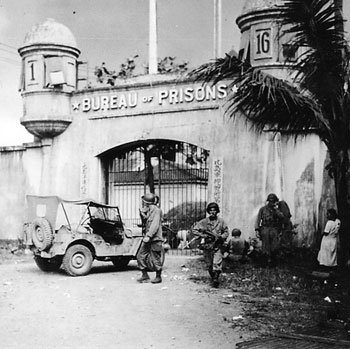

The First Miracle Walks With Me Into Old Bilibid Prison

Americans liberating old Bilibid Prison Americans liberating old Bilibid PrisonFebruary 1945 |

Liberated American POWs from Bilibid Liberated American POWs from Bilibid(February 1945) This is the way Don looked at 72lbs in Fort Santiago, March 1943 |

The first miracle was granted when I joined The Long March as I entered Old Bilibid Prison in April,1943. While in the Navy my normal weight was 190 lbs. Then, going into what was nicknamed "Hell University," my weight dropped to 140 lbs. But now, locked in Manila's Old Bilibid Prison, the scales read 72 lbs. For the rest of the war, I walked around looking behind me, to make sure no Kempe Tai was following me.

Cabanatuan POW Camp #1 - 1943

Cabanatuan POW Camp #1 - 1943From old Bilibid prison I was crowded into train boxcars and transported to the town of Cabanatuan, 90 kilometers north of Manila . We were packed so tight that when a man fainted from the intense heat inside the boxcar, it was almost impossible for him to fall down.

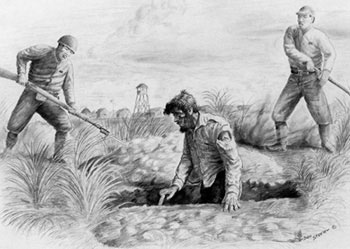

From Cabanatuan we walked the few miles to POW prison camp , Cabanatuan #1. I went into the Navy and Marine section of the camp. From barrack #4 I ended up in barrack. #6. We were put into 10 men groups to keep us from trying to escape. If you were lucky enough to escape, the other nine men would be immediately put to death. Needless to say no American would seek freedom under those conditions. Never the less two POWS escaped, causing the merciless deaths of eighteen of their buddies. I worked on a 300 acre farm that was hand worked by the POWS. We worked eight hours a day, five days a week. Due to a new more merciful Japanese Commandant the deaths dropped to a minimum. Because of the condition I was in when I came to Cabanatuan, had he not been there, I would not be writing this story.

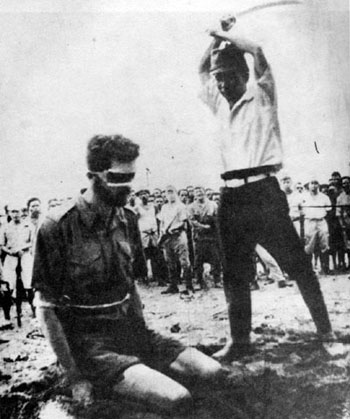

ABOVE: Punishment for trying to escape "dig your own grave" RIGHT: Another punishment for trying to escape "decapitation" |

|

He allowed the POWS to put on shows in our spare time. We even had a stage with lights and a enough musical instruments to supply a twelve piece band. Every Wednesday night the band played music. Every Saturday night it was show time, with the band supplying background music. We were blessed by the many talented guys the camp contained.

Because of the training I received from the Show Troop in Santa Tomas I was allowed to play a clown in many of Saturday night sketches. On Wednesday nights I sang with the band backing me up. The most fun was leading a quartet that sang like and as well as Tommy Dorsay's Pied Pipers. But most of all the warm feeling I would get when, once in a while, the men in my barracks would ask me to sing them to sleep.

The March Joins POWs Trapped In Hell Ships On The Sea

After the war, I learned that in the middle of 1942, the Long March moved to the high seas. Roughly 19,000 Allied POWs, captured in the Far East theater, started out for Japan in the holds of unmarked Japanese passenger and cargo ships. By the end of the war,11,000 of those POWs had died along the way. The POWs were packed, 600 men into a 50' x 50' ship's hold. They died of exposure, suffocation, thirst, starvation, strafing and bombing by Allied planes, or torpedoes from Allied submarines.

One Japanese ship, the Arisan Maru, carrying about 1,800 American men, was torpedoed by the American submarine USS Snook. The ship went down carrying almost all of the men to their death.

As the submarine moved in to look for survivors, the sub crew pulled five oil-soaked men aboard their submarine. The sub crew was horrified when they learned the men were American POWs. The unwitting monstrosity caused the captain to collapse and never command again.

The March Joins The Pows On The Mati Mati Maru

The Mati Mati Maru translates as "Wait Wait Ship"

The Mati Mati Maru translates as "Wait Wait Ship"In the last of June 1944 I was part of a five hundred man group that that was put together to be sent to only GOD knew where. We stood in boxcars again deployed to Manila and ended up in old Bilibid prison once more.

On July 1, 1944, one thousand American military POWs (including myself) were put on a Japanese freight ship moored in Manila Bay. The men were forced into two forward holds (500 per hold) at bayonet point. During the night the ship moved into the bay to anchor. The next morning I awoke with a headache, gasping for breath. I realized that the air in the hold was expanding quickly due to the heat of the sun hitting the ship, leaving no room for fresh air to enter the hold. It was only a matter of time before everyone suffocated.

With all the energy I could muster, I got up onto the deck of the ship. I can't explain what a relief it was to again breathe fresh air. I looked up at the bridge and, seeing people there, I started screaming my head off. Then a Japanese officer, with his pistol pointed at my head, ran towards me. I called, "Can you speak English?" He said, "Yes." I said, "If fresh air doesn't immediately reach all the men they will all die of suffocation." I told him to run his hand up and down in the doorway to feel the air escaping through the opening. Realizing what was happening, he asked me if I knew how to open the holds and I said yes.

So together we loosened enough canvas to triple the present doorway opening. The hot air from inside the hold rushed out. The stench was unbearable. The denser air outside was sucked down into the hold for circulation and relief. I was elated to find the operation worked. We ran to the other hold and repeated this task with the same results.

Now with light in the holds we could see the men and hear them groaning and starting to move. Many looked up and thanked us, some began crying, some saying , "Thank God." The emotion of that moment, of watching my buddies reviving, has remained with me all my life. The Japanese officer, standing by my side, said to me with a smile, "We were just in time."

I asked him if we could bring the American doctor up to check the men. The doctor told us that the men were suffering from severe dehydration and needed water. The Japanese began distributing the water to the men in the holds. I knew this would take some time and, feeling less apprehensive about the Japanese officer, I explained that Manila Bay was the natural habitat for the Great White Shark. I pointed out the jellyfish and also stingray in the water. I asked if he thought that any one in our condition would try to escape to swim to shore a mile away. He shook his head.

I had another plan. I asked him if he didn't think it would be best for these men, psychologically, to get up on deck, get fresh air and light as much as possible. He agreed. Feeling more confident, I asked him if we could bring up a 100 men at a time from each hold for an hour, rotate and replace them with another 100, giving each man at least two hours in the sunlight each day. He gave his permission.

Finishing his exams, the doctor said about 50 men needed more time on deck. I asked the officer to keep these men on deck at night for recuperation. So each night 91 of the POWs, 40 of the canvas holders, 50 of the patients, and myself overseeing, would be on deck. This gave badly needed space to the men below. This continued for 5 days, until we went to sea, on July 6th.

Because things ran without incident, the Japanese officer, with the ship now at sea, allowed open gangway. During the day about a third of the men were topside. During the night it was the canvas crew, the sick, and myself supervising on deck.

The trip from Manila to Moji Kyushu, Japan, our final destination, normally took an old freighter about nine or ten days. But because this ship constantly broke down, it had to put in to almost every port we passed and in the end, the journey took 57 days. The POWs nicknamed the ship, the "Mati Mati Maru," which meant "Wait! Wait! Ship."

This waiting turned out to be a blessing. Being unable to keep up with any convoy, a submarine's chosen target, the Mati Mati Maru could only stagger to Japan almost unnoticed. The Mati Mati Maru became known by all Japanese POWs as the Hell Ship that had a luxury cruise to Japan.

Even more, a torpedo struck the prison ship's side and did not explode, a miracle. On landing at Moji, we realized another miracle: only one man had died on the perilous trip to Japan. Yes! Even in Hell on Earth there can be miracles.

(See A and B under Appendices)

POW Slaves Sabotage And Survive In Nippon

From Moji, Kushu Island, Japan, our port of entry. We traveled at night in train passenger cars with drawn curtains. At midnight we arrived at the city of Omuta, Fukuoka, Kushyu, Japan, situated on the east shore of Arike Bay, 22 miles South West of Nagasaki. We left the train and walked over a mile though the walled enclosure of POW Camp #17.

In the morning I was given a green suit made of burlap, a cloth cap with a half inch thick felt liner, and a mine lamp holder. We were told to put on the suit, and sit in a chair. We were given a white placard with black I.D. numbers. I was told, from thereon, my name was changed to E-Sen-Bi-Yahco-Ju 1310.

From there I was lead to barrack Nee-Ju- Nee (22). The rooms had straw mat floors. The comforter was filled with shredded paper. Our pillow was a hard block made of straw.

In the morning we walked one mile to the mine to begin learning how to be a coal miner. Down in the confusion of the mine, I thought to myself, "How the Hell will I keep myself right side up under these forbidding conditions." Somehow I did.

POWs were forced to work 12 hours a day in the mines, factories, steel mills and ship yards, with three days off a month. They immediately realized they were in a position to fight the enemy again, but in a different way.

The POWs found they could not be watched every minute, so they became Suicide Commandos, sabatoging everything possible without getting caught. To be caught meant instant death. The stories are legend of what the desperate POWs were able to do to hurt Japan's war effort.

Japan's largest coal mine was in the city of Omuta. The Prison Camp #17 held 1,000 Americans, plus a mixture of 700 Australian, English, Dutch and Japanese POWs. All Allied POWs worked in the same areas as the Japanese workers, working with Japanese foremen.

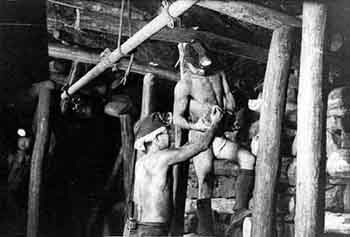

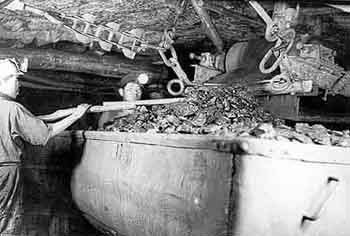

|

|

|

ABOVE LEFT:

Wood supports used in Japanese mines. In 1944 steel supports are used in the USA. ABOVE RIGHT: Chopping out the coal into a conveyor belt LEFT: Conveyor belt dropping coal onto coal car 1944-1945 |

The mine ran constantly. As the foremen left from time to time to perform other duties, the Americans were able to mix black rock with the coal, undetected. The coal was then fed into a huge crusher. Everyone knew the steel mill used this coal to heat the furnaces for making steel. The contaminated coal damaged grates, requiring replacement, which forced the mill to shut down for three days every month, giving the English POWs three days vacation.

The Japanese knew they had a language problem with all these nationalities. They knew most of the POWs had never seen a mine before, which could account for the coal and rock problem. The POWs knew this and it helped mask the risks they took. Their efforts probably reduced the steel mill production at least ten to fifteen percent.

In Japan, the Americans still suffered from the sickness and starvation of the Philippines. Now, in winter, in unheated barracks, they faced starvation and exposure to other life-threatening diseases. Yet, under these conditions, they were forced to slave in the mines and then die.

One thing became obvious: men who were disfigured by real mine accidents were excused to heal themselves in camp. Remember: The Razor was always screaming for more coal. Not only were the POWs under pressure, so were the Japanese miners. The Bontijos (mine foreman) kept yelling, "Hiyocko! Hiyocko!" (Faster! Faster!)

Birth of the Bone Crusher

Out of desperation and American ingenuity, an idea surfaced to protect their lives...at great risk. Hospital corpsman taught certain POWs how to safely break different bones without causing compound fractures that could tear the flesh and puncture the skin, resulting in blood poisoning. And so the Bone Crusher was born.

When a man was too sick with dysentery to slave on a killer detail, or go down into a condemned mine, he would make an appointment with his local friendly Bone Crusher. Others volunteered to help as needed in the fake accident. The coal mine really was dangerous. A year after the Americans left, 145 Japanese died in a mine collapse. Many Japanese were injured in the mine as well. This fact helped mask the fake accident problem. Many POWs had more than one accident during the two years they worked in the mine.

Breaking a POW's arm under the Bontijo's nose was not an accepted procedure. Planning an accident when they weren't sleeping or working might take a week. The POWs were dead serious about playing their part.

After the accident, the Bontijo beat the POW because Japan was desperate for workers, but now on bed rest, the prisoner's dysentery could be treated while the broken bone mended.

In June 1945 I had a bad case of dysentery. I knew the Japanese quack at the mine would only give a pass to a man, who, because of his physical condition, couldn't hold a shovel.

The American doctor told me I had to get out of the mine for him to heal me. He asked if there was a trained "Bone Crusher" close to me on my shift.

In the evening all involved gathered to plan the scene for what was to happen. I could have a broken collarbone, hand, arm, etc. I chose a broken foot. It was going to be done with a 40 lb steel roller smashed on my foot placed on a log. I had to find a log to fit under my instep so that when the roller hit my foot it would not be a compound fracture. If that happened, I could die of blood poisoning. It was to take place as we were building ceiling support walls in the mine. The plan was that the wall would collapse and a large rock would land on my foot. The next day the accident took place as planned. I fell into a dead faint as the bar hit me. As I lay there they went to tell the Japanese foreman that there had been an accident. He'd crawled off to sleep and they looked for him. We were in cahoots with the forman to let him get naps because the foreman worked days in the mine and as fire warden at night. He was exhausted. We kept a look-out to make sure no Japanese could surprise us. As soon as he was asleep the accident took place. When he came up my foot swelled up to the size of a balloon. It was obvious to him that I couldn't work anymore so he kicked me and called me "Baka!" (stupid) and went back to sleep. Although I was in pain I was exhilarated because I knew now they could cure my dysentery, and I wouldn't die in the mine.

The Massacre On An Island Called Palawan

Toward the end of the war, the POWs were told if the enemy tried to invade Japan, they would be put to death, for two reasons. First, in a long siege Japan could no longer feed them, and second, Japan would not tie down soldiers guarding prisoners.

When the war was over, the POWs in Japan learned chilling news about the island of Palawan in the Philippines. As American forces landed on Palawan in February 1945, 150 POWs were beaten back into a crude hole, an above ground air raid shelter. The Japanese guards threw gasoline into the hole and ignited it.

As the men came running out, screaming in agony, their clothes and bodies on fire, the Japanese guards machine-gunned them to death. Several men in the very back made it to the jungle and to the Americans retaking the island, becoming witnesses to what happened.

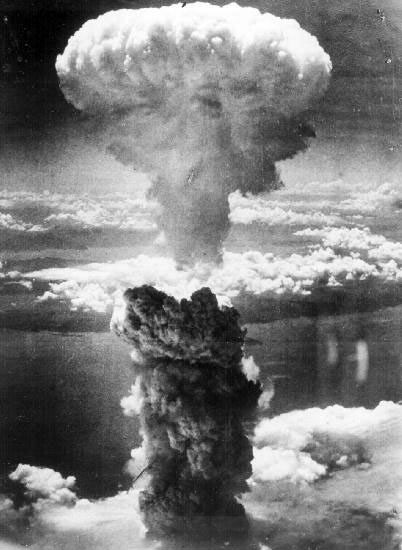

As far as I am concerned, a miracle happened. There was no invasion of Japan. The atom bombs exploded over Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The results of those bombs ended the war. While 94,000 Japanese were killed, the event saved the lives of over 165,000 Allied military and civilian prisoners held by the Japanese throughout the Far East. I was one of those.

The second prayer is answered when the atomic bomb

The second prayer is answered when the atomic bombends the war and saves my life

I had a ringside seat to witness the explosion of the A-bomb over Nagasaki. On mid-morning August 9, 1945, as I stood outside my barracks, I heard a plane fly over me, heading north. It flew so high I could hardly see it. Finally, by sight and sound, it disappeared but I continued to look in that direction. Suddenly the sound of an explosion and a bright flash of light caught my left ear and the corner of my left eye. I turned back to my left and looked slightly southwest over Arike Bay to see a large cloud rising rapidly in the sky over the mountain across the bay. It was over in the direction of Nagasaki. I couldn't see the city, as it is nestled in a valley between two mountains, about 22 miles away.

I stood there frozen at the overwhelming sight. While at the time I thought it was an ammunitions dump getting hit. It made me think of the explosion in Baffin Bay in Canada in WWI when an ammunition ship exploded and it killed everyone in a nine mile radius.

Now as I continued to stare watching the cloud rise higher than anything I'd ever seen, the cloud began to move in our direction due to the prevailing winds. Halfway out, the wind changed and moved the cloud 180 degrees back over Nagasaki and out into the China Sea. Later I learned it went 80,000 ft into the air. For me this was another miracle. The turn of the cloud saved all the Japanese and American POWs in the city of Omuta from death by radiation.

President Truman was told by our military authorities that an invasion of Japan would create over a million American military casualties. The casualties for the Japanese could be two to three million people. Faced with these numbers and realizing the American people could never handle such a catastrophe, Truman chose the Atomic bomb to end WWII.

Preparations for the hanging of Tojo,

Preparations for the hanging of Tojo,The Razor, Premier of Japan

at Macarthur's Order

By the War's end, The Razor's sentence had sent fifty-five percent of the POWs from Bataan and Corregidor to their graves. The death rate of American military captured elsewhere by Japan was nearly 40%. The death rate of American military POWs captured by the Germans was 1%. The Germans, more or less, followed the rules of the Geneva Convention, at least for American POWs.

The overwhelming disparity of death rates between the German and Japanese POWs screams to high heaven about the difference in care. For not following the Geneva Convention's Rules for proper treatment of POWs, General MacArthur caused the "Razor" to be hung by the neck in Suguma prison.

In our prison camp the Japanese commander told us that the war was over. He and the guards immediately left. The U.S. marines in camp took over guarding the camp. The first taste of freedom was from a naval carrier plane flying over the camp with flaps and wheels down, going as slow as possible. They tossed something out of the plane, dropping like a brick. It turned out to be a copy of Life magazine tied to a wrench. This was our first touch with America. This began our transformation from POW to being a free man.

A&P And Kroger Parachute Groceries To Our Back Door

B-29 dropping food and supplies by

B-29 dropping food and supplies byparachute over POW camp

Fukuoka #3, Tobata, Kyushu, Japan

September 13, 1945

A closer view

A closer viewdropping food and supplies

We were told to put PW in large letters surrounded by a circle on the ground. We used lime. This was to be a target for the planes to deliver food and supplies by air to us. Two days later the largest plane we'd ever seen, a B-29, flew over and dropped food and medical supplies. On its tail was a huge letter A. Soon we had formed a phrase, "The A&P store has gone to war and delivered its groceries at our front door." The next day another B-29 dropped more supplies and on its tail was the letter K. The new phrase was, "The Kroger store has gone to war and delivered the groceries to our back door."

B-29s dropping food and medical supplies

B-29s dropping food and medical suppliesOn Sept. 15, 1945 an American naval hospital ship arrived. Personnel came in and transferred the POWs to the ship to return to America. However I was not on that ship.

On September 6th, my buddy and I went to the train station in Omuta. From there we headed for Tokyo to welcome MacArthur on the 15th. We wanted to ask him where the hell he'd been? When we arrived in Moji, thousands of Japanese were trying to get through the tunnel to return to their homes. We ran into a Korean who had worked with us in the coal mine. He told us that he'd heard the Americans had landed in the direct opposite of where we were. They were in the south; we were in the north. We headed back from whence we came and continued on to Nagoya, Japan. From there we flew into Okinawa on September 8th.

Good Bye, Kempe Tai! Hi To The Gum Shoe Guy!

When the war was over, the newly freed POWs were stunned by the treatment they received by the repatriating American Military. The POWs were told they could not continue on their way home until they signed "certain papers." The papers forbid them, without government permission, to tell anyone what had happened to them while they were POWs. They could not even tell their families. The papers also stated if they disobeyed the governmental orders they would be punished. In disbelief and humiliation, they signed the papers.

(See Appendix A - Humiliation)

In Japan, my liberation was a joy beyond measure. However, upon arriving on Okinawa, it was a different story. There, as I lay on a cot in a U.S. Army tent hospital, an MP with a 45-revolver at his side broke my reverie. He indicated I was to follow him, which I did. I started to talk, but he indicated no talking. He led me into a room with a guy sitting at a desk. He wore an officer's uniform with no insignia, indicating that he was an intelligence agent. I began to sweat. I thought, "Oh, my GOD! Why has he need of me?"

He told me to take a seat and speak only when spoken to, answer all questions honestly, and everything would go fine. Otherwise things could get downright nasty and in a hurry. He gave me a cigarette and lit it for me. Then he sat back in his chair and stared at me. This was different, I thought. Tanaka San had done the same thing for me. But to get my attention, Tanaka San was more to the point. He smashed the burning cigarette into my face.

The guy started by telling me all the things that I had told another interviewer the day before. When he finished, he looked at me for my admission. I nodded yes. Next, he repeated that I was a radioman at NPO at the Naval radio station at Cavite and my last duty station was assignment at the Office of Naval Intelligence and Censorship at the Yokohama Species Bank in Manila. He looked at me again. I nodded yes.

Now he asked me if I ever operated on a circuit at NPO. I told him I didn't operate on a circuit at NPO because I was just out of radio school and I was not fast enough. I was okay for inter-fleet traffic, which is thirty-five words a minute. The NPO fleet circuit traffic is fifty words a minute.

Then he asked me if I ever practiced sending on one of NPO's circuits? I told him the most stupid thing you could do is practice on a circuit at NPO. Interfering with naval business could get you a court martial, and in a hurry. Then he switched subjects to ask if I ever listened to traffic going to Pearl Harbor or Washington, D.C.

I thought to myself that I've got to give this guy something to get him off my back. I told him I did a couple of times just to hear what it was like to listen to real code being sent. Most of it was five-letter code groups. I could not understand what that was. At radio school we listened to closed circuit machine code. There was no static or fading in and out like real traffic being affected by atmospheric conditions. I told him the station didn't allow students to stay around long.

He looked at me with a scowl and asked if I didn't listen more than a couple of times. "Did you listen to plain language going to D.C. or Pearl?" I thought, "This guy has a fixation with D.C. and Pearl, what is he trying to get out of me?" I told him that stuff going to those places was too fast for me, and that I only listened to local traffic. He sat back in his chair, looking like he had no more places to go.

Thank God, I thought, he is never going to find out what I knew before the war started. As I started to relax, he picked up a sheet of paper and shoved it in my face. He told me to read what the paper said and then sign my name, rank and service number.

I read the letter. At the end, I was staggered. The letter had two paragraphs. The first paragraph read: "While you are in the Navy you must swear you will never talk about any former military matters. If you do, you will be given a general court martial. Your sentence will be the time you spend in a Naval prison."

The second paragraph read: "If you leave the Navy and you talk about former military information, you give the Navy the right to pick you up, sentence you, and then place you in a Naval prison."

The guy asked me if I understood what was in that letter. I told him I did. Then I asked him what would happen if I didn't sign the letter. He told me he would have the MP place me in the stockade and I would sit there and rot and not leave this island until I signed the letter. I signed the letter. Then he told me that if I minded my Ps and Qs for the rest of my life, I had nothing to fear. Talk, and you get to fear ten years in a Naval prison. He didn't offer me a copy of the letter and I didn't ask for one.

God! Talk about injustice. Two days before, I was under the boot of the dreaded Kempe Tai. Now I'm in dread of the boot of the American Gestapo. Later, I realized that officer had sealed my lips from ever testifying at the Pearl Harbor Investigation, which was yet to happen.

In a bar in San Francisco where Don's weight is about 140 lbs.

In a bar in San Francisco where Don's weight is about 140 lbs.As a POW, Don's weight dropped to 72 lbs. in Fort Santiago.

It rose to 120 lbs. in Cabanatuan and dropped to 81 lbs. in

the Japanese coal mines.

From Okinawa I was flown to Manila. As we flew over the city I was in shock. I cried out, "Oh my GOD!" Manila, Senorita Manila, the "Pearl of the Orient" lay destroyed. "Oh my god Manila is dead," I cried out. Now one of the most beautiful cities in the world was gone. MacArthur had made her an open city to save her. All was for naught.

The most devastated city in WWII was not Hiroshima, nor Nagasaki, or Warsaw, it was Manila. Over a hundred thousand were killed and wounded inside of two weeks. In deep sadness I flew out Manila across the beautiful blue Pacific Ocean to Oakland CA on the largest sea plane in service in the world at that time. From there I rode a train to Chicago and then on into Lansing Michigan, my home.

The Third Miracle... Elaine Marie Is There For Me!

For me, because of more miracles than I could count, it was, "Home is the sailor. Home from the sea. Again safe in America, the Land of the Free."

On October 1, 1945, when I got off the train in Lansing, Michigan, I walked onto Michigan Avenue and looked at the state capital, overwhelmed that I was back home. The War was really over. I walked into the same grill that I visited when I left Lansing, at 2:00 a.m. in 1940. The same waitress who said goodbye to me in 1940 said hello to me.

I could not find my father's phone number and called my aunt. We cried and I took a cab to her house. The first thing we shared was our grief about my brother. He died in the war. My aunt said that I had to see my father. At one time he had a flag in his window for two dead sons in the War. And now I am alive.

When we arrived at my dad's house, it was full of people who came to see me. I was claustrophobic and I hollered, "Where is the bathroom?" "Right behind you." As I went through the door I noticed stuck in the woodwork a letter.

I immediately recognized the perfect Palmer-method writing of my school teacher. I pulled the envelope out and in the upper left corner it read, E. M. Aho, Appleline Street, Dearborn, Michigan. I turned and hollered at my dad , "My God, how did you get this letter?" He answered, "When Elaine came to Lansing to teach school, she was in a night club where I was and and came to the counter when the announcer called out my name, Don Rutter. I told her that my son was a prisoner of war. Later your picture was in the newspaper, and another school teacher sent Elaine the clipping. Elaine sent this letter to me, your dad. She was so happy that you were alive, saying if he comes to Dearborn, she would be happy to say hello." I read that letter a thousand times and died a thousand times thinking that when I called, a little kid would answer and say, "Mommy, someone wants to talk to you," and then I would die.

Finally I called, expecting the worst. A voice I heard so long ago said, "Hello, who's this?" And I said, "It's me." She said, "I am so glad you are still alive," and now I lied to her. I said to her, "I'm coming to Detroit in about two weeks, on a Friday, to go for exams at the V.A. (The truth was that I figured it would be two weeks before my hair was long enough to comb.) Was she doing anything that night?" She said, "No." "Could I take you out for dinner and to a dance that night?" She said yes. I'm coming back to life now. I seized the opportunity to say to her, "As long as I am in Dearborn, could I have a date with you Saturday?" She said yes. Now I went for broke. I said as long as long as I am still there how about a date for Sunday? She said yes. I thanked her and said goodbye. I put the phone down and howled for joy!

Then the day came and, and I rolled along with Doris Day singing , "I'm Going to Take a Sentimental Journey." Finally I arrived in Dearborn and I was overwhelmed and hollered "God, what am I going to say?" The light turned green and I turned right. I saw the sign saying, "Say It With Flowers." I hollered, "Thank you, Father." At the flower shop there was a large container holding long-stemmed American Beauty Roses. I said, I will take them all. She said, "Boy, some girl is going to get a big surprise." With both hands I picked up the bundled six-dozen roses and marched out the door singing for joy, "I'm going to take a sentimental journey."

Late in the afternoon I drove to Elaine's school after the kids went home. I walked through the office door, moved the roses to the side to see where I was going, and found the secretary in shock. "You must be here to see Miss Aho." She got up and led me to Elaine's room and opened the door.

"Miss Aho, someone is here to see you." I stood there by the door and two soft warm female hands slipped over mine to take the roses, and I died. She lowered the roses and after seven long years I was looking at a face that was a little older and more beautiful, with the serenity of a woman who knows who she is. I half whispered, "Hi," and she said, "Hi."

Immediately we were shoved aside by six or seven other school teachers and the secretary rushing into the room. They took the roses out of Elaine's hands placing them on the little kindergarten table. She walked over to the table with them to admire the roses. Then I walked over and sat in one of the small chairs. All these young single women were bending over admiring the roses and here I was sitting admiring the long-stemmed legs of these women bending over the the long-stemmed roses.

We said goodbye, the teachers all hugging Elaine, but not me. Damn. We took her roses to her home and I waited while she changed, and then we took off for a bar that she knew.

The miracle of the third prayer is Elaine and I are

The miracle of the third prayer is Elaine and I areengaged this evening October 15, 1945

We sat down at the bar and I chose six songs from the jute box, "Sentimental Journey", "It's a long long time", "Till the End of Time", and , "There I've Said It Again", followed by "What's New", and the last was "Where are you?" The songs began and without a word we listened to the songs, me looking into the mirror across the bar with a look that asked, "Are you listening to the words?" as she stirred her drink.

We ended up in one of the most beautiful nightclubs in downtown Detroit, ordered dinner, and at 9:00 p.m. one of our songs began, "Until the end of time." I asked her to dance and was shaking so hard inside I was afraid Elaine would feel it. Her soft voluptuous body pressed against me, she leaned into me and placed her cheek against my chest, her perfumed hair in my face. As we stood there, again I died. In the middle of dancing, a male voice screamed out, "Kaotsky!" the Japanese word for "Attention!" The music stopped. Silence. I was in the middle of the most wonderful dream and I was waking up a prisoner of war. Again I heard "Kaotsky!" I turned and looked at a man in a sailor suit who had gained a 100 pounds since I saw him in 1944 in POW Cabanatuan Camp #1. I let go of Elaine. We ran to each other in a bear hug. At the POW camp we became buddies when we discovered we both were in love with school teachers.

Some men yelled, "What the Hell is going on?" I turned to a guy and told him our story. He said, "Oh my God. I'm going crazy seeing all uniforms and all the hugging and kissing going on in my place. I fought in WWI and when I came home I had a girl still waiting for me. And tonight she is sitting there all alone. Tell you what I am going to do. I'm going to walk out that door, and take that girl and start hugging and kissing her too. You can stay here as long as you want, and everything, all the food and drinks are on the house." My buddy's quiet girl blurted out, "Oh my God. All my life I wondered what would it be like to be part of a miracle. Now here the four of us are together. They came half way around the world to come back to us. And we were there to hold them in our arms again. Us from Cleveland on our honeymoon and you from Dearborn in the same Detroit nightclub. How in God's world could something like this happen without God. We have our miracles." And everyone cheered! Finally we walked out the door and parted, each couple to go their own way. "See you around!" And we took off for Dearborn.

We parked in front of her house under a dark street lamp. The moon was shining down on us. She sat in her corner and I sat in mine with my elbow resting on the steering wheel. I said to her, "Elaine, I have not changed. In fact looking at you now, I didn't realize how much more I could love you as I am loving you now. And if you can't once more tell me that you love me it's okay. I will open my door, then open your door and I will go with you to the door of your house and I won't try to hold you or kiss you. I will take you to the door as my mother taught me. I will just say thank you and say goodbye and I will never bother you again. Elaine, what do you say to those words?" She fell sobbing on my chest. "I never stopped loving you." I was thinking this is deja vu. After seven years it's happening all over again, her sobbing on my chest. And all the time, I was saying, "Thank you Father," overwhelmed with everything that happened the past seven years. Instantly, seven years of longing were gone.

The miracle of the fourth

The miracle of the fourthprayer is my first child,

Suzanne Elaine Rutter is

born in Lansing, Michigan

on January 3, 1947

(I was lucky enough to

have two more children,

Roger and Jan).

Now as this was happening the third miracle was happening and I knew there was no way that I could run away from God. Otherwise how could I be standing there holding Elaine. I realized that He loves me. In spite of all my faults and actions, he gave me Elaine.