CHARLES MARINUS SUNDBY (1908 - 1948)

(CNAC November 4, 1942 - December 21, 1948)

(Made Captain - December 27, 1942)

(Hump Flights - 591)

|

Updated 5-17-2020 |

|

Background music to this page can be controlled here. "National Anthem of Denmark" |

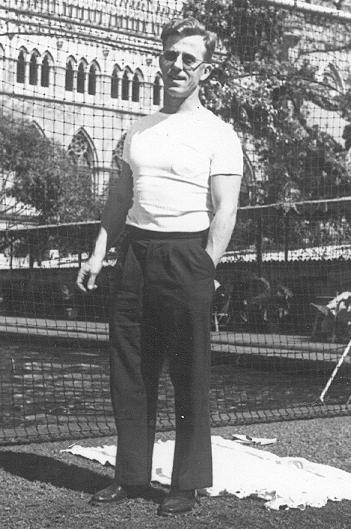

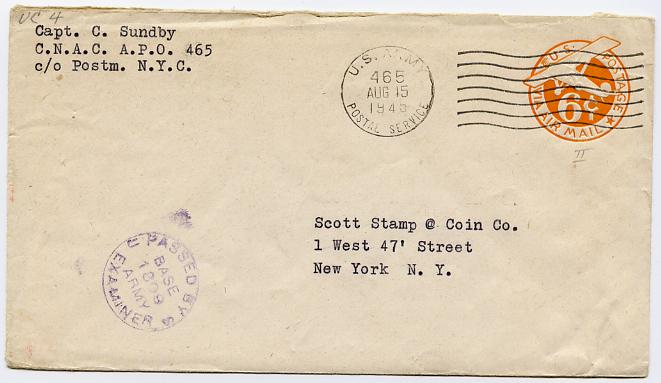

In the 1943-45 log book of Don McBride, Charles listed his address as: C. Sundby Copenhagen Denmark  Charlie Sundby at the Royal Calcutta Swiming Club (Photo Courtesy of Jim Dalby)  From Gene Banning's list of 8/31/00: "... Danish, from RAF Ferry Command, prom capt 3/43 (actually the date was December 27, 1942); killed in DC-4 crash during inst approach to Hongkong on 12/21/48." October 12, 2005 Dear Mr. Moore, This is a very exciting moment for me. Charles Sundby was my great uncle and the much loved uncle of my father, Douglas Charles Sundby. For years I had heard stories about uncle Charles, including a sketchy account of his death in China in 1948. I am due to visit my dad in California next month and will question him at length for more information, which I will pass on to you as appropriate to your site. What a thrill to have a picture of Charles in his prime! Please add me to the CNAC distribution list. Sincere thanks, Eric Charles Sundby, Ph. D. E-mail sundbyec@shaw.ca Charles Marinus Sundby By Rechs Ann Sundby Pedersen October 17, 2007 Charles Marinus Sundby was my father. I was very young when he died, and sadly, I have no memory of him. This biography is based on documents and personal papers: passports, certificates, flight log books, newspaper and magazine articles, official and private letters, contracts. My father’s career is mentioned in books and on the Internet. In those accounts, I have found outright mistakes plus omissions that can be misleading. Using the primary sources that I inherited when my mother died, I have tried to make an accurate account of his professional life. Update: August 13, 2017 Charles Marinus Sundby, by Rechs Ann Sundby Pedersen. “Some people sit in an office chair day in and day out, arrive at 9:00-- if Long Bridge is not up, or the [commuter]-train is not delayed-- leave at 5:00 sharp, and are content with that. There are others whose blood always races in their veins and their inborn need for adventure simply does not let up before they have seen the sun set in the four corners of the world. To that latter group belongs the former Flight Lieutenant in the Danish Navy, C. Sundby…” (Interview in FLYV February 1946) Charles Marinus Sundby, my father, joined CNAC on November 4, 1942. As was the usual practice, he was hired as a co-pilot with the understanding he could be promoted to Captain if he proved his” ability and qualifications to be in command of an aircraft.” (Contract) In early December 1942, my father arrived at CNAC operations in Assam and began flying the Hump. After twelve Hump flights, he flew down to CNAC offices in Calcutta, checked out on December 21, and six days later learned that he was promoted to Captain. (Logbook and W.L. Bond “Memorandum…” Wings over Asia. V.5 pg 89.) From the interview in FLYV magazine in February 1946: “[Interviewer] What was your assignment? [My father] We flew Chinese soldiers, who were to be trained in India; it was a stretch of 510 miles. Because the Japanese held Burma, it was necessary to make a detour. The route went from the province of Kunming to Assam in north eastern India, way up the source of the Brahmaputra River. The planes we flew were C-47 and C-46, transport versions of the DC-3 and the large Curtiss Commander, respectively. The Americans had supplied the Chinese with this modern materiel in accordance with the Lend-Lease Act. Forty Chinese soldiers were packed on board these planes each time. [Interviewer] Were you often shot at by the Japanese? [My father] No, in that regard, the route we flew was fairly safe. As a rule we went up to an elevation of 18-20,000 feet during most of the flight over the Himalayas, which lasted 3 hours and 20 minutes. We lost only two planes because of Japanese action. Whereas, the weather conditions were the cause of losing around thirty transport planes.” From his first Hump flight on December 11 1942 to his last Hump flight on December 11, 1945, (with home leave from May to October 1944), my father made 591 Hump flights and flew 2,488:30 hours for CNAC. When my father came to CNAC, he brought a variety of work experience with him. Born in Copenhagen in 1908, my father began his working life as a teenager. With the goal of becoming an officer in the Danish merchant marine, he began working on merchant ships. In those days, education for a merchant marine officer began with acquiring practical experience, called “sailing time.” It consisted of working on ships—particularly ocean-going sailing ships-- and moving up the ranks. After the practical requirement was fulfilled, my father completed the academic part of his education at what was called a “navigation school.” He graduated from the Copenhagen Navigation School with papers qualifying him as an officer and potentially a captain in 1934. That same year, the Danish Naval Air Service changed its requirements for admission to its pilot training program, allowing graduates from a navigation school to be considered for the program. My father applied to and was accepted into the 1934 class of pilot hopefuls. In December 1935, he completed the program to become a Flight Lieutenant in the Naval Air Service. During his time in the Service, he flew seaplanes-- mainly Heinkel HE8s and to a lesser extent, a Dornier Wal. He participated in several special assignments, including the photographic mapping of Greenland and the Lauge Koch Expedition to the Artic, where he flew reconnaissance flights in the open-cockpit Heinkel. Contemporaneous film of the Greenland Aerial Survey and the Koch Expedition can be viewed on the Danish Defense Command’s website. My father’s career in the Naval Air Service effectively ended, when Germany invaded Denmark on April 9, 1940. Hoping to join the Allies, my father and another pilot escaped occupied Denmark one night shortly after the invasion. They took a boat and crossed the sound between Denmark and Sweden, narrowly escaping detection by a German patrol boat. Travelling across Sweden and up to northern Norway, they connected with the free Norwegian forces. They were told that the Norwegian forces could not use them. From there they sailed to Britain where they applied to the RAF. They were not accepted, no reason given. Running low on funds, the two pilots signed on a Danish ship bound for South Africa. Once there, they applied to the South African Air Force and were told “maybe”. Not having received an answer, they sailed on to India where they contacted the Norwegian Embassy. Shortly thereafter they received acceptance telegrams from both the South Africans and the Norwegians. Accepting the Norwegians, they travelled to Canada to become instructors at Little Norway, an elementary flight training camp established in Ontario. In October 1940 when my father arrived in Canada, the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan(BCATP), under the command of the Royal Canadian Air Force, was just getting underway and in need of flight instructors. On October 30, 1940, my father joined the RCAF as a Flying Officer and instructor in the BCATP. After three short postings, he was transferred to the Occupational Training Squadron at Patricia Bay, British Columbia. There he served primarily as a flight instructor for Grumman Goose, Submarine Stranraer, and Noorduyn Norseman. He himself qualified on Lockheed Hudson, Lockheed Electra 10, and Bolingbroke. In February 1942, my father resigned from the RCAF, with a total RCAF flying time of 676:40 hours. In May 1942, my father joined the RAF Ferry Command as a captain. (Civilian airline titles were used in the Ferry Command.) Taking off from the east coast of Canada, he crossed the Atlantic three times to deliver bombers to the U.K.-- 2 Lockheed Venturas and a B-25. He also flew the southeastern route—down South America, across the Pacific to Africa—to deliver a Lockheed Hudson IV bomber to Cairo, Egypt. When he left the Ferry Command at the end of October 1942 to join CNAC, he had logged 161:30 hours in the Ferry Command. After the end WWII, my father continued to fly for CNAC. My parents first lived in India; when the Company moved back to China, they moved along with it to Shanghai. Flying primarily Douglas C-54 Skymasters, my father flew CNAC’s routes in China, Asia, and across the Pacific to San Francisco. On December 21, 1948, the situation in Shanghai was tense. The Communist army was moving closer to the city; CNAC had told its employees to prepare to move out their families; my mother was packing our belongings; and my father was to fly refugees from Shanghai to Hong Kong. Before takeoff on that day, my father was given an inaccurate weather report for Hong Kong, stating clear weather. Approaching Hong Kong, he encountered poor flying conditions with heavy clouds and very poor visibility and crashed into the top of a mountain on Basalt Island. All on board were killed. Here is additional information about the Basalt Island Crash by Tobias Brown. I have donated my father’ s archive of documents and photos, along with a more extensive biography and a fuller account of the Basalt Island crash, to the Aviation Library & Louis A. Turpen Aviation Museum at the San Francisco International Airport. P.S. An Act of Kindness A few days before my father died, a Chinese friend came to see him. The man had with him a certificate for preferred shares in the American company, Shanghai Power, which he wanted to sell to my father. My father knew that the shares would soon be worthless, but he also knew that the man needed money badly. He bought the shares. The next day the man came again, saying that the shares would soon have no value and wanting to return the money. My father refused to take the money back, saying, in effect, “a deal is a deal.” The shares did indeed become worthless and the certificate lay in a trunk for twenty years. When China opened up to the West, my mother remembered the certificate and checked with a stockbroker to see if it was worth anything. The answer was “Maybe. Hang on to it.” In December 1979, my mother saw an article in the “San Francisco Chronicle” announcing “expropriation payments” for holders of Shanghai Power preferred shares. Over the next few years, my mother received a nice sum of money for the worthless shares that my father had bought out of kindness so many years before. Rechs Ann came across several photo's that belonged to her parents. Hopeully, someone "out there" might recognize some of these faces. Click here to see these photos.  or would like to be added to the CNAC e-mail distribution list, please let the CNAC Web Editor, Tom Moore, know. Thanks! |