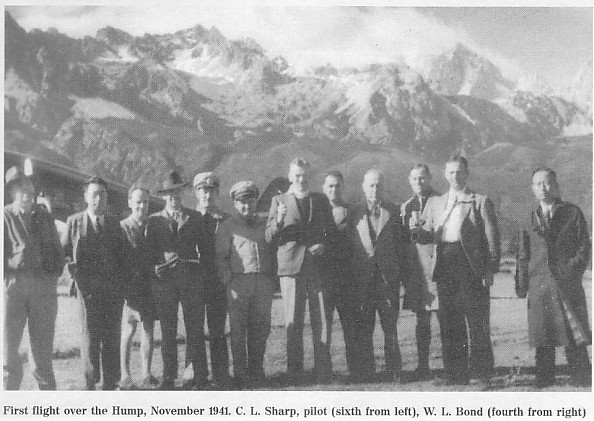

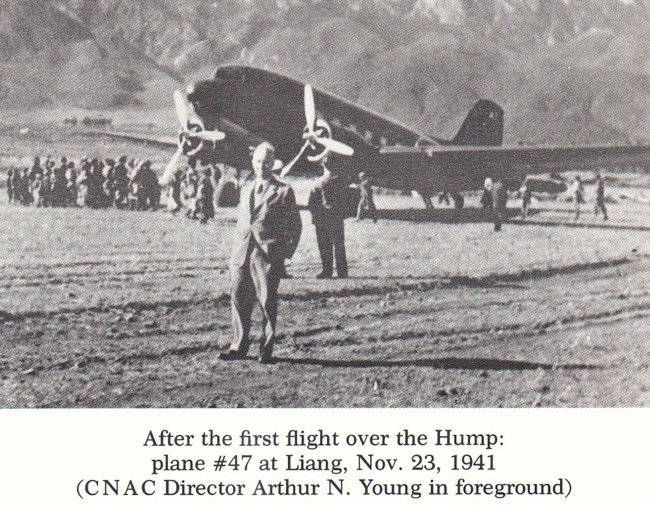

Somewhere over the Hump (Courtesy of Audrene and Bob Sherwood) (All rights reserved Including Reproduction in any form. Copyright @ 1971 by The China National Aviation Association Foundation.) (The plane was a DC-3) In late 1940 or early 1941, it became evident that alternate supply routes into China would be needed since the British foothold in Hongkong was precarious. CNAC assigned Charles L. Sharp and Hugh L. Woods to reconnoiter a new lifeline. As Captain Woods saw it, there were four fundamental requirements: The new air base would have to be at or near a seaport, riverport or railhead; the distance into China would have to be within range of the aircraft and short enough for economic operations; the base had to be comparatively secure from Japanese attack; it had to be in a country which would permit CNAC to operate. The obvious choice was the tea-producing region of Upper Assam in India. This meant that CNAC planes would have to fly over the roof of the world without weather forecasting and exposed to such terrible hazards as polar air masses which could assume the form of violent blizzards and 125 mile-an-hour crosswinds. General Henry H. ("Hap") Arnold, Chief of the Army Air Corps, was convinced by Brigadier General Clayton Bissell that the Assam-Chungking route was not feasible. Bissell proposed instead a 4,000-mile leapfrog operation from New Delhi and thence parallel to the main Himalayan ranges on the Chinese side. Had this alternative been adopted, it would have involved minimum pay loads and might well have forced China out of the war. Captain Woods made the first exploratory flight from Assam into Free China, noting the locations and elevation of all mountain ranges. Frank ("Dude") Higgs, the prototype of "Dude" Hennick in Milton Caniff's "Terry and the Pirates" comic strip, was co-pilot and Joe Loh was radio operator. The only passenger was CNAC Vice President William Langhorne Bond. November 30, 1941 FIRST FLIGHT OVER THE HUMP by Arthur N. Young, former Director of China National Aviation Corporation and Financial Adviser to China (The plane was a DC-3) Arrangements for the flight, to explore new air and land routes into China, had been under discussion for several months. The British made a condition that we should not fly over Tibetan territory without Tibetan consent, and this was not sought as it would have taken more time and in any case a route over Tibet was not necessary. Finally the details were settled. The flight would go from Lashio, Northern Shan States, to Northeast Assam; thence over Fort Hertz, the most northerly post in Burma territory; and thence to Chungtien in Yunnan, Likiang and Kunming. British officers from India were to accompany the flight. The party was to assemble at Lashio on November 20. On reaching Lashio on that date, we found that the officers from India had been delayed by trouble with the BOAC plane from Calcutta. They were to arrive at Rangoon on the 21st. They did so, but the bomber flying them to Lashio could not make it before dark as the weather was stormy, and was forced down 100 miles away. They finally arrived at 10:00 a.m. on the 22nd. Meanwhile, we wondered whether we could go at all. The weather was stormy at Lashio, and we feared it would be similar to the north. The time of a DC-3 plane is precious, and an important schedule had been delayed. But on the morning of the 22nd the weather was improving and we decided to go. The party consisted of two British officers from India; five air officers from Singapore and Burma; the British air attache to China; a road expert of the Chinese Ministry of Communications; and W.L. Bond, K.I. Nieh (assistant operations manager of CNAC) and myself representing CNAC. Also there was a servant fired from the CNAC Hostel at Lashio who had to be returned to Hong Kong -- and who was taken along because there was room, and who slept nearly the whole time! The pilot was Chuck Sharp, co-pilot de Kantzow (an Australian), and the radioman was Chang. Altogether we were 16. Before leaving Lashio we prepared about 20 "first flight" airmail covers for the philatelists of the party, and sent them to the Lashio post office. By 1:00 p.m. we were ready, and took off in bright weather with broken clouds. We flew over heavily wooded rolling country, with occasional green streams in the jungle. Now and then we saw clearing. Soon we came to Namkham, with red-roofed houses, and then to Loiwing just inside the China frontier. Because of the aircraft factory there, the frontier was marked with huge white crosses to give notice to Jap planes. When the place was raided, however, a year ago, the Japs disregarded the frontier and flew over Burma, even dropping a bomb or two on Burma soil. We could still see some marks of the bombing. Before long we came to Bhamo, an important port on the Irrawaddy River, which is the point of departure for the historic route of Marco Polo into Yunnan via Tengyueh, Tali and Kunming. Large barges and river boats were seen. The rise and fall of the river is very great, and as this is low water season we saw huge sandbars. We went up the valley to Myitkyina, the end of the northern branch of Burma railways. The river narrowed and boats were smaller. Myitkyina is a pretty and well laid out town in a broad valley. From there we bore northwest towards upper Assam in India. The country became rougher and wilder. There is no really useful land connection between Burma and India, as Burma is afraid of Indian immigration. As we gained height to cross the 8,000 foot pass we could see higher mountains to the north, about 12,000 feet high. West of our route are the famous jade mines. Coming to the Patkai Bum range, separating Burma from India, we found steep gorges with dark colored streams far below us. As we approached India, we saw occasional clearings and villages on the more level parts of the mountains. In broken clouds we skimmed the tops of the passes in the jumbled mountains, dodging through holes in the clouds. There were some fine rainbows to be seen. The mountain villages were unlike anything I had seen before, the buildings having long oval rounded roofs, some quite big. Soon we could look out on the huge plain of Assam. It is watered by many rivers, the largest being the Brahmaputra, which is several miles wide in places. The land is closely cultivated, like the lower Yangtze plain of China, and there are many trees. We landed at 4:20 p.m., the first flight to cross the Burma-India frontier. Also we were the first big plane to land at the field in Assam. When we had landed, after circling the field twice, officials came hurrying to meet us, followed by most of the British colony of the area. As it was Saturday afternoon, most of them were at the nearby club. They had received a stupid telegram from Calcutta saying that we would come the next day -- as Calcutta had thought we could not make it earlier. So they were not ready to receive us. But they scurried around and found places for us to stay -- no small task for so many in a small community. The radioman and servant stayed with the plane and slept on board, with an Indian guard outside. Bondie and I stayed with Dr. F.C. McCombie, an elderly and hospitable Scotch doctor to one of the tea plantations. He had a large house built on stilts of steel, this having been done in the old days when it was believed that malaria was caused by miasma near the ground. He lives all alone and in grand style, with plenty of servants and good food. Tea is the big interest in Asam. The tea plants are a striking sight from the air, as they are closely packed together and the tops of the plants all cut down to the same level of about four feet. A tea field looks like a huge linoleum run with its regular pattern. At intervals, there are nitrogenous trees planted to help the soil.  left to right unknown, unknown, unknown, unknown, Syd de Kantzow, Charles Sharp, unknown, unknown, W. L. Bond, unknown, unknown and unknown ("Wings for an Embattled China" by W. Langhorne Bond) Assam where we were is near to the frontier of northeast India, which few people have crossed. Beyond are wild tribes. The country of the Abors has never been penetrated by white men. The Abors wear no clothes, though it sometimes gets quite cold; shoot poisoned arrows; and collect heads. As we were to fly close to their country, we were not keen about a forced landing. In this valley there is plenty of game -- wild elephants, which often come in and destroy villages because they have learned that they can find rice there; tigers; leopards; buffalo; wild pigs; etc. Also there are plenty of snakes of many kinds. In southeastern Assam is the wettest place in the world, Cherraponji. On looking at the Calcutta paper, I saw from the weather report that to November 20 Cherraponji had had a rainfall of 442.8 inches, or 19.4 inches above average to date. The heavy rainfall is due to some peculiarity of topography which causes heavy precipitation from the monsoon. At Shellong nearby rainfall was only 92.8 inches to date. From Sadiya, the end of the Assam railway connecting with Calcutta, the trail goes on into the country of the tribes and thence into Tibet and western China. Few people have made that crossing, which is very arduous and takes months. We were to do it in three and a half hours. On Sunday morning, before we took off, Chuck Sharp gave a special flight to our hosts and to some of the natives. It was the first flight for most of them, and they enjoyed seeing their valley from the air. While waiting at the field, a large gathering of natives lined up at the edge to see the plane. In the crowd were a few natives with spears from the tribes. I bought one for five rupees and hope some time to bring it back to the U.S. The handle is covered with fuzzy red material, one end has a sharp thin point, and the other end has a broad spearhead. It is a vicious weapon, and meanwhile I am well defended in Chungking. We took off on Sunday, November 23, at 10:45 and headed east toward Fort Hertz. We flew over more tea plantations and farms, and as we climbed through the clouds we could begin to see the nearer and lower Himalayas to the north. Here we were about 500 miles east of Everest. soon we could see the first snow mountains to the northeast, on the border of Assam, in glimpses through the clouds. At this stage the cloud formations were very fine, with huge piled-up masses, but they were no help in seeing. A storm had been moving up from Calcutta, but we were apparently well ahead of it. As we flew on, the Brahamaputra valley narrowed and the mountains became higher and more jumbled. We crossed the border range, with mountains 12,500 feet high and some snow in sight. Then we came to a fine broad valley and were over Fort Hertz about an hour after our start. Fort Hertz is a small settlement, the most northerly post in Burma, at the northwest corner of the famous "Triangle" formed by two branches of the Irrawaddy River, in which country there has been great difficulty of pacification. Crossing the northern part of the Triangle, we could see higher snow mountains to the north of the valley, perhaps 16,000 feet high. Soon we came to the easterly branch of the Irrawaddy, a big blue-black stream with many rapids in a deep gorge. The after passing through clouds we came out into clearer weather to see far ahead the huge ranges running north and south that separate the three great rivers, the Salween, Mekong and Yangtze. It is a remarkable phenomenon of geography that here the three rivers run parallel within a space of 30 to 40 miles. All three rise in the wastes of Tibet. The Salween flows through Burma, China and again Burma to empty into the Bay of Bengal at Moulmein. The Mekong flows through China, into Indo-China, to Saigon. The Yangtze of course flows by Chungking to Shanghai on the China Sea. At one point in the air we could spot the gorges of all three. As the snowy ridge of the first range east of the Salween loomed up, the co-pilot came back to urge us not to move around much as the plane was going high. The pilot, co-pilot and radioman took three of our four oxygen tanks, leaving one for use by the rest of us if needed. Soon we were over the Salween, in a very deep gorge but still perhaps 5,000 feet above sea level. We were flying at about 14,000. We turned north to fly for a while parallel with the snowy range and above the gorge. It was a grand sight, with the sides of the gorge so steep that much of it was in shadow even about 1:00 p.m. The river looked like a thin black ribbon, with occasional white streaks showing rapids. I was taking pictures from time to time, but this was not easy as the condensation of breath in the plane fogged the windows. Still some of the pictures came out fairly well. Then we turned east again toward the Mekong, and as the weather was clear we could cross the range without going above 14,000 feet, though we had expected to go much higher. We flew past bare rocky heights with snow just outside the windows of the plane. In all directions we could see higher mountains, but at this point those in sight probably were not over about 18,000 feet. We found the Mekong valley broader and less wild appearing, but in all this country there was no sign of any inhabitants. A forced landing would have been just too bad for us. Crossing the range east of the Mekong we were soon over the Yangtze valley. Here the valley was much broader and we saw small villages and some cultivation. Flying northeast, we saw on the far horizon some very high peaks, three together rising above the other heights. These we learned later were near Atuntze in northern Yunnan and were 24,000 to 25,000 feet high. Soon we spotted Chungtien, which we wished to observe from the air. It is in a broad valley and is a Tibetan style settlement. The temple was a remarkable sight from the air, built on a high hill in the midst of the valley, with huge square structures and a great amount of gold in sight. It was surrounded by other square and rectangular buildings. The whole effect was different from that of any place I have ever seen. I wanted a picture, but the course of the plan did not give a proper point of vantage. This country is on the route to Tibet, the mountains of which we had seen from the air. Turning south we flew among high mountains to Likiang in a broad valley of the River of Golden Sand. This is really a gold-producing country, and during the war we have bought and exported much of its gold to buy needed supplies abroad. At Likiang we were to pick up Dr. Rock (Dr. Joseph F. C. Rock), the explorer, who has been there for some time. He is a great authority on this country and the native tribes and Tibetans. We had telegraphed him that we would come at about this time, and to be ready. We circled the valley and flew up and down the road without seeing any sign of him. We landed at the "airfield" in the north of the valley -- a bare level space that is a natural field, but without any improvements and no settlement near. Bondie wanted to say, "Dr. Rock, I presume." But we found no sign of him and no one at the landing ground but a crowd of native tribesmen and Tibetans. We wanted to wait for him, but the radioman had word of a storm at Kunming and the pilot was unwilling to make a night landing, so after waiting as long as we could and having no word, we reluctantly had to leave. At the landing field we all got out and walked around. I took some pictures which came out well. The natives were much interested in the big plane, as they had of course never seen one and probably never even heard of one. I wonder what they thought. Also what did the savages think in the wilds over which we had flown? After walking around and resting at Likiang for over an hour, and looking in all directions for some sign of Dr. Rock, we climbed into the plane. Bondie and I with others ran down the field making signs to the natives to get off the track we were to us as a take-off. This was not easy as people were streaming across the field to see the great sight. But when the engines started up, they began to get the idea and to understand our signs. When starting the engines, one of us stood on each side to keep people away from the propellers. The noise and wind and dust then did the rest. We climbed into the plane, hoping that no one would have to be run down on the runway as we were taking off. At 8,400 feet and with a non-too-long runway, we could not stop once the take-off had begun, and if anyone were in the way it would just be his or her hard luck. But luckily the way was clear, and we made an excellent take-off and were on the way to Kunming. We arrived just at dusk, picking our way past the storms. It had been a wonderful day.  Tail #47 is a DC-3 HELP!!! (Photo Courtesy of William Leary) (Ed: Please check back as more photos will be added.) August 22, 2004 Hi Tom, We just returned from a trip to China. In Kunming we were surprised to see the popularity of the term "Hump" as related to the Hump Route. Everyone seems to know what it is and they call it the same. There is a Hump clothing line, we saw a Hump Café and a Hump Bar. The bar's walls were covered with photos of C46's, the Himalayas, pilots, crashes, etc. The lady who owned it was delighted when we were able to add to her collection. And there is a line of coffee called Hump Coffee. They sent us home with several bags and cans of it. And the Chinese are in love with the Flying Tigers. Regards, Lydia & Dick Rossi  If you would like to share any information about the "Hump" or would like to be added to the CNAC e-mail distribution list, please let the CNAC Web Editor, Tom Moore, know. Thanks! |