Names mentioned:

Carey Bowles

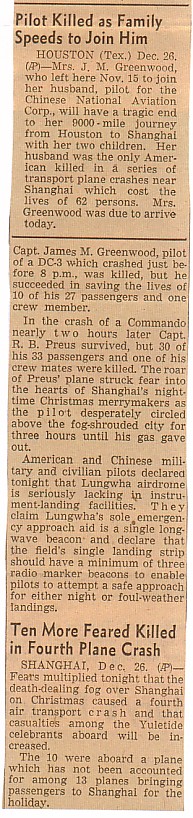

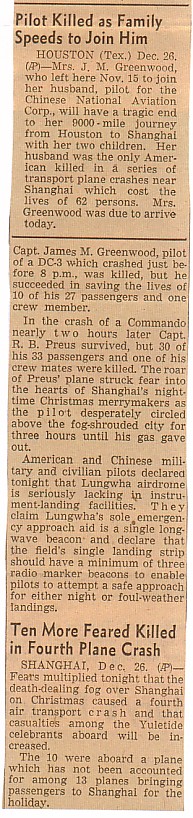

Capt. Greenwood

Rolf Preus

Tommy Wing

Joe Michiels

The following is a portion of a letter written by Tom Reynolds to his wife, Damaris Reynolds. Thanks Damaris.

"Shanghai

January 2, 1947

....

Now, for the terrible tragedy of Christmas night. I had gone out to Lunghwa at 6:00 that morning, intending to leave for Nanking on the first plane out. The weather was wicked. Ak heavy for enveloped everything. Even driving out to the field was hazardous, considering the driver I had. I hoped however that with sun-up the fog might lift enough to get the planes in the air. After waiting until about 11:00 o'clock, and then taking a look at the weather map, I came back to the Woods' house. The fog got progressively heavier, and at 1:00 p.m. when we went out to a reception at one of the pilot's homes, it had turned into a heavy drizzle so dense it was not possible to see more than a few feet ahead and there was no ceiling. The Woods and I returned home for an early lunch after which we all turned in for naps. At 5:30 we were back downstairs for a cup of coffee, whiling away the time before getting dressed to go to the Tweedy's for Christmas dinner. The phone rang at about 6:45 and it was some one calling Woody to give him the incredible news that one of CATC's (Central Air Transport Corporation - ex Eurasia) had cracked up at Kiangwan while trying to get in, killing all ten occupants and probably the occupants of a house it hit before burning up. The next great shock was the news that three CNAC planes were overhead trying to get in. When Woody repeated this I immediately went outside to look at the weather. It was not possible to see across the compound, 100 feet or so away. While I was out there a plane flew overhead in the direction of Lunghwa. The ceiling was below the top of a low building just across the street. The condition was zero-zero.

Woody phoned Tweedy, then he and I rushed out to Lunghwa. "Mac" MacDonald (McDonald), Chief Pilot, and three of his assistants were already there. Mac was in the tower and one of the three planes, an unconverted DC-3 was low overhead circling the field. Mac was attempting to contact him by radiophone but was having great difficulty as the plane's radio equipment was not operating properly. Positive communication had been established by CW (dot-and-dash). The plane was running low on gas as it had been released from Hankow for Nanking but had been unable to get into Nanking in three or four tries, before coming on to Shanghai. It had made several attempts to land at Kiangwan by GCA (ground control approach -- radar) but was unsuccessful because of radiophone trouble. The GCA unit could receive the plane all right, but the plane could not get messages from the ground in turn. The pilot, Captain Greenwood, then came over to Lunghwa knowing that he had no alternative by that time. The nearest clear weather alternate field was Tsingtao, but he had insufficient gas to get there by this time. Apparently he decided against that course earlier because Tsingtao does not have any field lights for night operation. There was hope too that an occasional break in weather might occur, according to CNAC and Kiangwan forecasts. In summary up to this point, Greenwood had to attempt to get in at Shanghai, and Lunghwa was a better choice than Kiangwan.

For something like forty-five minutes the plane flew around in the fog overhead. He made several attempts to "feel" his way down to a sight of the lights. Once he came in so low right overhead I was almost on the verge of diving into a mudhole. Instead of clearing, the weather seemed to get worse. By this time the drizzle was thick and without let-up. Finally Greenwood told Mac on the radio that he was so low on gas that he was coming in. I had been up on the hanger roof for the past few minutes, but with this news went down on the field with Gordon Tweedy. The fire engine was standing by near the runway, and ambulances were on their way to the field. The whole scene was tense to the breaking point. I recalled my own take-off from Lunghwa just twelve years before and the subsequent events (crash) at that time. It was certain that this plane would never get in whole except by the greatest good luck; the airport beacon seemed determined to reach out and help the pilot in; but at best its beams could only penetrate a small distance into the gray mass overhead and all around us. All was deathly silent on the field. The only sound was that of the plane in the distance, getting louder and louder as it approached the field from out of the southwest. As it came nearer I did my sincerest best to offer a silent prayer. I am sure everyone around me was doing the same thing at that moment. I am equally sure thay were as scared as I -- of what, I don't know because we were safe and sound on the ground. Nevertheless I was shaking so hard I could hardly conceal it from those around me.

The engines grew to a roar, and by now the whistling of the airfoils was clearly audible. It seemed long-since that he must have dropped below the field's level. Suddenly there was a dull red cone in the fog about two hundred yards away, followed in an instant by a muffled boom; then for an instant the silence was complete. Gordon turned to me in the rain and said in a hushed boice, "God, oh God" with what was unmistakably a reverent inspiration. In a matter of only seconds Woody picked us up in his car and we rushed down the runway to where there were several small fires burning. There was no large blaze for the reason that there had been no gas left in the plane to burn. Even though we were at the scene in less than a minute, the fire truck had already got there and men were dragging out extinguishers and hose. The rudder which is covered with fabric was burning, and odd pieces of fabric scattered about the ground were on fire, but the blaze was quickly put out.

Within the next few minutes all survivors and all bodies were removed and on their way into the city. Dr. Hoey, CNAC's doctor, whom I had met while he was with the Firestone Company in Liberia, did a magnificent job which was all the more remarkable because it was raining so hard and everything so deep in mud.

I went back up to the Control Tower. Mac had just received word that the second of the three CNAC planes had just been brought in safely by the GCA at Kiangwan. That performance was a wonderful one. A few minutes earlier the GCA staff had recommended that the pilot attempt to make Okinawa rather than try Kiangwan even with the help of GCA. The ceiling was about 50 feet and visibility a quarter-mile. Mac was in constant contact with the third CNAC plane overhead, a C-46 (Curtiss Comando). This plane's radiophone was operating on low frequency but not on the VHF (Very high frequency) required for GCA. The pilot reckoned he would fall short of Okinawa by about 12 minutes.

He flew back and forth over the field several times, coming down as low as he dared. The Lunghwa Pagoda and chimneys of a nearby cement plant were serious hazards in the soup that hid them. At one time at this stage, the fog seemed to break up a little and we got a glimpse of the plane as it roared overhead at about 500 or 600 feet. The pilot saw the runway lights and had a positive fix on his position. Four of the pilots who had come out to the field (Pottschmidt, Watson, Shilling and one other) had gone down to the south end of the runway over which the plane would come in to land. The plane, after getting his fix, made a dry run through his approach procedure and as he passed over these boys they fired Very Shells which the pilot saw clearly. He asked that they not be fired on his next approach as they would blanket out the runway lights which, incidentally, were only oil smudge pots. Next the pilot climbed up to the altitude called for in the standard approach procedure. Mac was talking to him all the time. He was calm and confident. We on the ground felt re-assured. I was back up on the hangar roof next to the Control Tower once again, listening for Mac as the plane went out for its final leg of the let down. As the pilot made his turn into the final leg, Mac asked him not to reply to Mac's transmissions. Mac instructed him calmly to come on down the final leg at 110 miles an hour, and at 150 feet altitude as he passed over the inner marker - a radio beacon near the approach end of the runway.

I distinctly heard him coming in. His altitude sounded all right in the distance and fog. Mac all the time was talking to him. The fog had seemed to lighten a little. When it seemed he was nearing the inner marker there was a sudden dull thud-like sound and then again that awful silence. The wreckage and survivors were located a few hours later directly in line with the runway, but about two miles short of it. The heavy rain and the fact that that part of the country is cut criss-cross with canals delayed the search and rescue. It was finally necessary to use landing craft and crash-boats sent up by the Navy for this purpose even though the plane had crashed on the Lunghwa side of the river. It had hit a Chinese school which fortunately was empty at that hour of the night. The pilot and several others were removed to the hospital and are coming along well at the present time. The death toll for the three crashes stands at 71; and 16 survivors to date. I think this was the worst day in the history of commercial aviation.

Gordon Tweedy and his staff have been working like trojans since, assembling all the facts preparatory to their formal hearing. The Chinese press, Ministry of Communications, Control Yuan, People's Political Council, and even one of the local Chinese courts are already conducting their own "investigations". General Shen, CNAC's Managing Director, was ill all last week unable to see anyone, but the American members of his staff have done their best to proceed impartially with a true finding. There are rumors that the Control Yuan is attempting to establish criminal negligence against Shen and Woody, the Operations Manager -- even that Shen may be shot and Woody imprisoned. The papers (Chinese) of course have made endless unfounded accusions against everyone whose name they could learn. While I do not expect that any drastic action will be taken in regard to the Americnas, Shen may be treated roughly, as with so much outcry from so many quarters it seems almost inevitable that someone must be the scapegoat. George Sellett is following this angle carefully, thus our Americans are in good hands.

While in Nanking after the accidents I studiously avoided the several Chinese agencies, as they certainly would have pressed me for some expression which I naturally could not nor would not attempt to give until at least the present investigation is completed and the pertinent facts correlated. Through friends however I was able to get "reactions" from the Minister of Communications. He, being responsible for civil aviation, is in a tight spot and much worried. He regretted that Bondie was not here, with his experience and the confidence everyone has in him, though for Bondie's sake I was grateful he is in Florida. The tension would certainly do his poor health no good.

|

Shanghai, Lunghwa Airport: The Air Disaster on Christmas Day 1946

By Ronald Ian Kliene - Senior Control Tower Operator, China National Aviation Corporation, Lunghwa, Shanghai.

If you can share any information about this night

or would like to be added to the CNAC e-mail distribution list,

please let the CNAC Web Editor, Tom Moore, know.

Thanks!

|